Late last year, I was in South Africa attending Buntwani 2015. As always, it was great meeting new people and catching up with old friends. Sadly, some of those old ‘friends’ included many of the issues we seem to continually face in the development sector—ones that don’t seem to want to go away. I wrote about this in “Retweet, recycle, repeat” and “What to do when the yelling stops?” recently.

In the development sector, we need to begin the shift from repetitive dialogue to constructive action. Tweet This Quote

One of the sessions I proposed was aimed at kickstarting discussion around some of these historical issues. I quote from almost every technology-for-development conference of the past ten years:

- We need to stop reinventing wheels.

- We need to share and learn from each other.

- We should collaborate more.

- We should work more closely with local people.

- We should avoid using tech for tech’s sake.

- We should break out of our silos.

- We need to put an end to ‘pilotitus’ (a scenario where many NGOs are funded for relatively similar, but isolated pilot projects, resulting in no resources left for scaling them up).

As anyone who’s read my blog over the last few years will know, I’ve been writing about most of these issues for a long time. Sadly, it seems like we’re still as far away as ever to solving many of them meaningfully, despite the fact that they’re almost impossible to ignore. The fact that some people might be happy with the status quo is one of the reasons I called the current state of affairs ICT4D’s “inconvenient truth.”

As JFK famously said, ‘We choose to go to the moon not because it is easy, but because it is hard.’ Tweet This Quote

When I launched my Donors Charter back in 2014, I asked how we might break the cycle of “technology for development becoming a sector full of replication, failed pilots, poorly thought-out projects, secrecy and near-zero levels of collaboration.” I agree with those who say these are big, hard problems but, as JFK famously said, “We choose to go to the moon not because it is easy, but because it is hard.” We need to have the same attitude.

Over the years, I’ve gradually pulled together a number of ideas and arguments for how we might begin to solve some of these issues and begin the shift from repetitive dialogue to constructive action. For the first time in one place, here’s the beginnings of my manifesto, or Six-Point Plan for Change. Together, these will form the first ever strategy for The kiwanja Foundation—but more on that later.

1. Fully develop and deploy a Donors Charter.

Under pressure to support ‘innovative’ ideas, and often under pressure to spend their large budgets, donors often resort to funding projects they shouldn’t. What we end up with is a sector full of replication, failed pilots, secrecy and near-zero levels of collaboration.

Today, we know enough about what works and what doesn’t to be far more targeted in what is funded. Tweet This Quote

This negatively impacts not only other poorly-planned initiatives, but it also complicates things for the better ones. On top of all that, it confuses the end user who is expected to make sense of the hundreds of tools that end up on offer. The policy of funding many in the hope that the odd one shines through—the so-called “let a thousand flowers bloom” scenario—belongs to an earlier era. Today, we know enough about what works and what doesn’t to be far more targeted in what is funded and supported.

Donors can fix this by agreeing to ask potential grantees a dozen very simple (mostly yes/no) questions, answers which will determine whether or not the project was ready for funding. You can download a checklist of the questions, and read more, on the Donors Charter website.

2. Create a shared foundation for under-spent funds.

Of course, if donors ceased funding badly thought-out projects they would either have to give more to those worthy of support, or they would have a surplus. Giving more to the most promising projects isn’t a bad idea, but any surplus would still be a major problem for any donor.

Investors invest in people, not products or ideas. Tweet This Quote

At the moment, many of the larger government development agencies would likely pump anything left over into the World Bank, or another large institution that could absorb it, which in most cases isn’t particularly strategic. Many smaller foundations also have funds left to spend, leading to a scramble to disburse them before the end of the financial year in order to protect their donor/non-profit/501c3 status. Smart fundraising teams often know this, meaning easy pickings for any that can get short concept papers together within a matter of hours. Again, a situation not too strategic for the donor.

Instead of this, could donors create a shared foundation that could absorb some of these underspends, and then use those funds for some other (perhaps bolder) strategic programs, such as those outlined here? Or commit to giving them to NGOs in the global south?

3. A program of investment in people.

We hear it all the time. Investors invest in people, not products or ideas. Marty Zwilling, a veteran start-up mentor, describes people as the great competitive advantage. I wonder what the non-profit world might learn from people like him?

The vast majority, if not all, non-profit foundations and donors are project-focused. In contrast to many angel and traditional investors, they’re primarily interested in the products and ideas. It doesn’t matter too much who has them, as the hundreds of online development competitions and challenges testify. These investments in products and ideas, however helpful and generous they may be, almost always miss one key thing—investment in the person.

What would the non-profit sector achieve with a VC-style approach? Tweet This Quote

I can’t help but wonder what the non-profit sector might achieve with a VC-style approach. Imagine if each year a large, private foundation picked half-a-dozen or so people working in global development—people with a track record of vision, thought-leadership and execution working and living anywhere in the world—and supported them in a similar way? Imagine being able to free up some of the greatest minds, conventional and unconventional, to imagine and deliver their own vision of development into the future?

Freeing them up financially would, in the same way as the MacArthur Fellowship, allow them to be bold and brave with their ideas, and in the same way “enable recipients to exercise their own creative instincts for the benefit of human society.” Isn’t benefiting human society, in essence, what the non-profit world is all about? More on my thoughts on funding people not projects can be found in this Stanford Social Innovation Review article.

4. Create an independent M&E body.

Knowing what works and what doesn’t, and to what extent, is crucial if we’re to continually improve global development efforts. Grand programs such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)—and the new Social Development Goals (SDGs)—only make sense if we’re able to track progress. In a recent Guardian article, Bjorn Lomborg asks if we met the MDGs and which targets were closest. If we’re honest, we don’t really know the answers yet (and we may not for some time). According to Bjorn:

We have consensus in global development that M&E is critical, and while there are plenty of people, projects and organizations proposing and working on their own solutions, there is seemingly little coordination. Given that donors, more than anyone, ought to want to know if their money is being spent well, why not create and fund an independent M&E body to once and for all agree on standards, approaches and tools?

Knowing what works and what doesn’t, and to what extent, is crucial to continually improve global development efforts. Tweet This Quote

Each donor could provide a small percentage of funding to cover operating costs, which would likely be no more than a few million dollars each year. Then, make it a condition of all the grants they provide that the M&E body is consulted by the grantee and a sensible, effective plan put in place to get baseline data for a project. Finally, have some kind of evaluation carried out at the end. This information could then be published online, furthering our understanding and strengthening best practices. In the same way that donors often insist that technology projects are open sourced (a debate for another day), they could insist all projects subject themselves to a certain agreed standard of monitoring and evaluation.

5. Future scenario planning.

In a recent interview for a paper on the Principles for Digital Development, I suggested that the best way forward for our sector would be to paint a picture of what we see the future of ICT4D to be, and then to put policies and practice in place to enable us to meaningfully work towards that future. For arguments sake, we could pick 2030 as our date, which would neatly tie in with the SDGs.

If we analyzed social media to pick out the main themes and opinions (this might be the quickest way to get an early sense of the kind of future people are talking about, or perhaps the most honest one), then I’d hazard a guess that keywords and phrases would include things like: local empowerment, building local capacity, people solving their own problems, bottom-up development, appropriate technology, etc. Using this, we might say:

From here, we could agree on a timetable of how we achieve this over a 14 year period—how we build local capacity and institutions, gradually increasing levels of funding to local organizations (which currently amounts to only a couple percent of all humanitarian aid spending), support initiatives that build engineering capacity in-country, slowly wean Western institutions (NGOs, academia, etc.) off the practice of trying to save the developing world with fancy new technologies, and work towards a better balance where outsiders take on a new, more back-seat role in this new future.

How about (for starters) an event, or a conference, to agree on this future? Then, wider collaboration and consultations to decide how we might get to a future we all agree on? And then, for all parties to commit to owning it and executing on it?

6. Towards an anthropology of innovation.

I’ve always maintained that my chance encounter, and subsequent training, in social anthropology has had a huge influence in the way I go about my work. The concept of participant observation—simply watching and learning from a distance, without attempting to directly impact or directly ask specific questions—should be an essential step in gaining local understanding, and empathy, before any attempt to solve anything.

Projects can succeed or fail on the realization of their relative impacts on target communities. Tweet This Quote

It’s widely recognized that projects can succeed or fail on the realization of their relative impacts on target communities. Development anthropology (one of many branches of anthropology) is seen as an increasingly important element in determining these positive and negative impacts. In the commercial ICT sector—particularly within emerging market divisions—it is now not uncommon to find anthropologists working within the corridors of high-tech companies. Intel and Nokia are two such examples. Just as large development projects can fail if aid agencies fail to understand their target communities, commercial products can fail if companies fail to understand the very same people. In this case, these people simply go by a different name—customers.

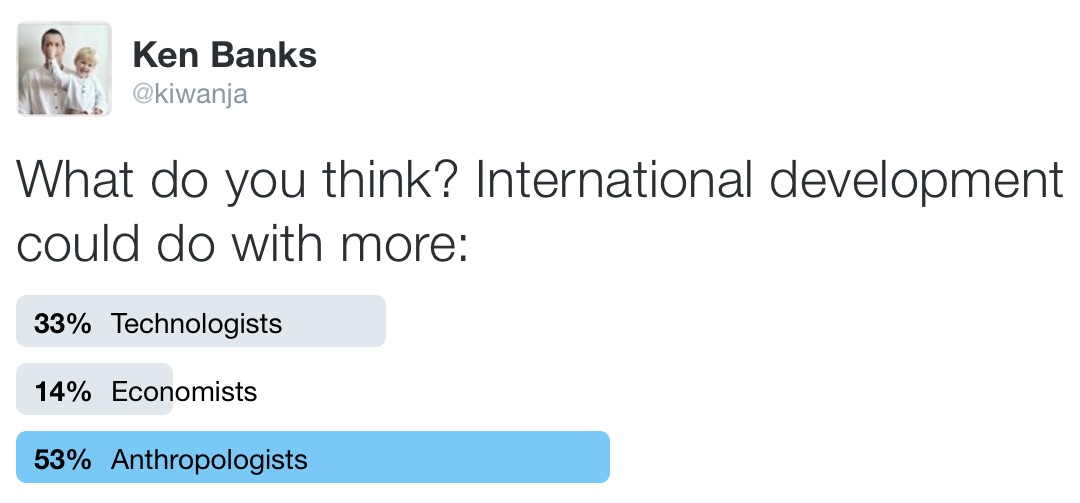

With the need for empathy and local understanding as key pillars in today’s ‘user centered design’ approach to social innovation, there is much we can learn from anthropology. Yet, the discipline remains largely on the sidelines. In my recent Twitter poll, the need for anthropologists came top. One thing we need to do is figure out how to mainstream the discipline in all aspects of ICT4D and global development projects—to the point where they’re not the exception, but the rule. No team should be complete without an anthropologist, or the input of an anthropologist.

No team should be complete without an anthropologist, or the input of an anthropologist. Tweet This Quote

Back in 2007, during my time at Stanford University, I incorporated The kiwanja Foundation (the original home of FrontlineSMS, now remodeled into SIMLab). Almost ten years later, I think I finally have something closely resembling a launch strategy for the Foundation. The majority of these ideas are well formed, and some (such as the Donors Charter) have been ‘launched,’ although resources to fully promote them have been somewhat limited. With a little seed funding, one day I hope to continue with those I’ve started and execute on the others.

The 10th anniversary would be a great time to do this. That’s just under one year and counting. There’s nothing quite like setting yourself a challenge. Any adventurous funders out there with a little cash left over at the end of their financial year?

A version of this post originally appeared on Ken’s blog.