My first brush with technology-for-development, almost twenty years ago, wasn’t on the potential of the Internet, or how mobile phones were going to change, well, everything. To be honest, neither were really on the development radar in any meaningful way back then. It’s almost funny to imagine a time when that was the case.

No, my first contact with what was to become a career in information and communication technologies for development (ICT4D) started off with an essay on the failure of plough and cook stove projects across Africa. I was struck by the beauty of simple, locally appropriate solutions and amazed at how development experts just didn’t seem (or want) to get it. Many of their failed initiatives seemed more like a reaction against them—that, as experts, they were expected to come out with something the opposite of simple, primitive, practical. This they did, but very little of it ever worked.

It was around this time that I also came across the work of E. F. Schumacher and his brilliant 1973 book, Small is Beautiful. The lessons in his book apply just as much today in a world dominated by digital technologies—a world he would never have imagined back then.

Our obsession with the latest shiny technology hasn’t gone away, either. History repeats itself, and despite being armed with a range of tools and solutions that work, experts still appear to rebel against them because they’re digitally too simple, primitive, or practical. And, again, many of their alternative “innovative” solutions simply don’t work.

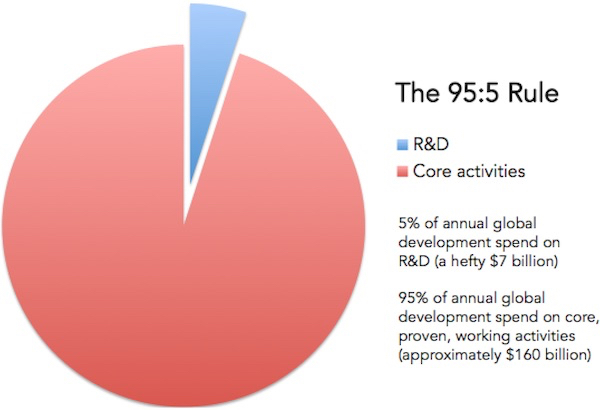

Sure, there needs to be a degree of emphasis on new tools, new solutions, new ways of tackling old problems. This—the R&D side of the development machine—is essential but it needs to be kept in balance. The average R&D spend among top UK companies in a recent survey was five percent. No company in its right mind would spend most of its money on research and development and ignore its bread and butter, namely its current products and services, and current customers.

What if the global development sector make a commitment to spend, say, five percent of its funding on blue sky, high-tech, high-risk, forward-looking ideas, and commit the rest to funding the really simple, primitive, appropriate solutions we already have that are proven to work? Five percent of global development spending is still a few billion dollars, more than enough to invest in the “next big thing.”

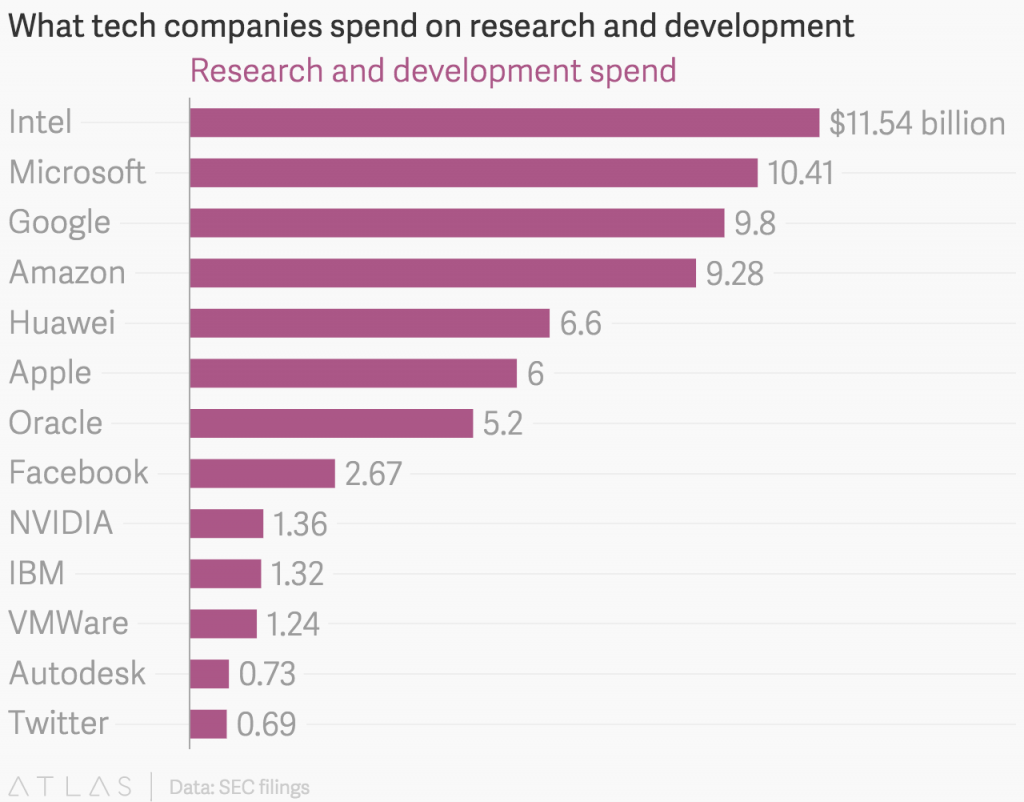

And what if it pooled these funds and created a single Global Development R&D Fund? A better-coordinated approach might result in better outcomes, and it could better manage its external communications. The amount available would compare quite favorably with R&D spends of the bigger tech companies. (source: Atlas)

Right now, with an increasing big data, drones, and wearables obsession (among many others), you get the sense that global development R&D lacks coordination and spends too much of its time, energy, focus and resources on high-risk ideas. While it toys around with the next big thing, people are going to bed hungry, dying of treatable diseases, at school with no pens or books, or drinking polluted water. All of these things can be put right with the technologies we possess today, but they’re not. I’ve never understood why. We should only allow ourselves the luxury of looking to the future once we’ve fixed the solvable problems of the present.

We should only allow ourselves the luxury of looking to the future once we’ve fixed the solvable problems of the present. Tweet This Quote

While the development community needs to naturally look ahead, it also needs to remember the people suffering today—those who might not be around to reap the benefits of any cool drone, big data, or wearable solution of the future. Every life matters, after all. You get a sense that in the development space, R&D spending is way out of control as it feeds its obsession with cool, shiny, and innovative.

While the development community needs to naturally look ahead, it also needs to remember the people suffering today. Tweet This Quote

So let’s keep that R&D budget in check, be more open with how much is being spent on speculative new ideas that may go nowhere, and make sure we don’t forget our bread and butter—our current (working) products and services, and our current customers—the poor, marginalized and vulnerable out there who, through no fault of their own, desperately need our help. Today.

This article published in 2015. It has been reposted to inspire further conversation.