It’s well-known these days that the standard venture capital (VC) model of investing ignores some fundamental laws of math, at the expense of their limited partner investors (LPs). Dave McClure’s post sums it up well, and I’ll distill the argument even further:

- Typical funds invest in 30 or so startups.

- One in 100 become the home runs which drive returns.

- Thus, VCs need to get lucky for any single fund to not lose money for LPs.

- Still, this is a rational strategy for any VC who can raise a large fund, because they earn management fees based on size of fund, regardless of whether LPs lose money (to wit: a $100M fund earns $20M in management fees for VCs).

So, are VCs good at investing in startups, or is it all just luck?

Are VCs good at investing in startups, or is it all just luck? Tweet This Quote

This same question has been asked in the realm of professional poker, where it’s quite easy to mistake luck for skill. Every year, thousands of players enter World Series of Poker events, trying to win a coveted championship bracelet. Of all the winners of the 36 events played in 2003, there were six superstars who won multiple events. Given the thousands of people competing for just 36 bracelets, what are the chances of someone winning two or more events in the same year?

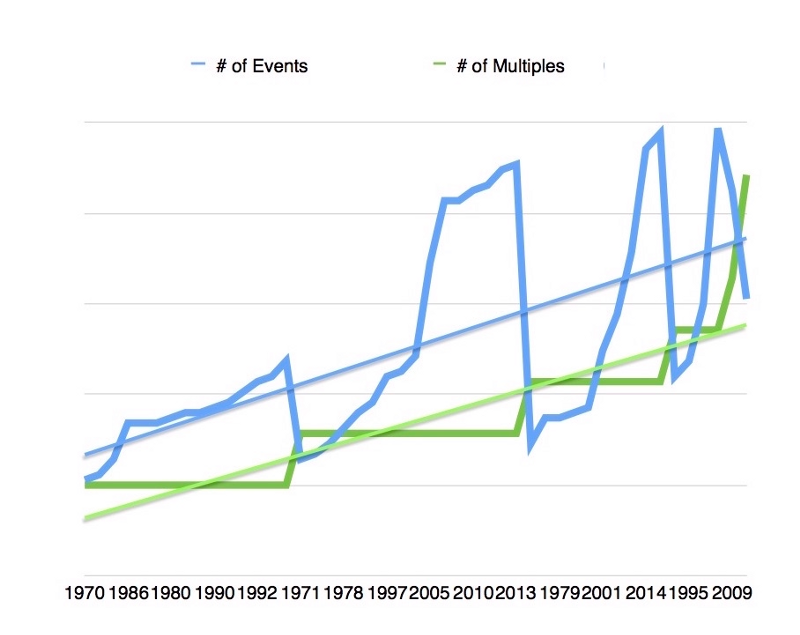

Turns out, pretty good. Here’s a graphical depiction of the correlation between multiples and number of events:

In other words, multiple winners are a statistical artifact, a.k.a. luck. Sure, skill plays a role as to which players are more likely to win multiple times. But do you see how easy it is to take small samples of data and find spurious patterns confirming the “skill hypothesis?”

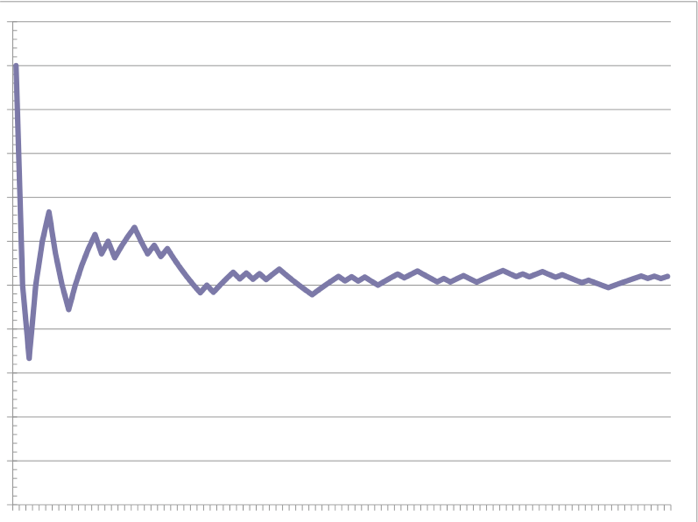

In poker we use concepts from statistics: expected value (EV) is a measure of skill, and variance is the amount of luck. According to the Law of Large Numbers, the longer you play, the lower variance becomes, and the more likely your poker results (or investment returns) will converge to your EV. See how this looks visually as you move from left (“short run”) to right (“long run”).

In games of skill that have a big luck component – like poker and venture capital – long run results are about skill, but in the short run, luck dominates.

In games of skill that have a big luck component – like poker and venture capital – long run results are about skill, but in the short run, luck dominates. Tweet This Quote

Freakonomics guru, Steven Levitt, measured the amount of luck versus skill for poker, and concluded, “Players identified a priori as being highly skilled achieved an average return on investment of over 30 percent.” The key here is identified a priori.

Nobody has done a proper analysis like this for the VC industry yet, as the data is too closely guarded by VCs (hmm, I wonder why?). However, that will soon change as interpolative databases like Crunchbase and CB Insights become complete enough to run the analysis. Here’s what I think they will find:

- While the “long run” in poker is measured in months/years, in VC it’s measured in decades/lifetimes.

- While some VCs are much more skillful than others at achieving returns, their skill edge is NOT in picking winners.

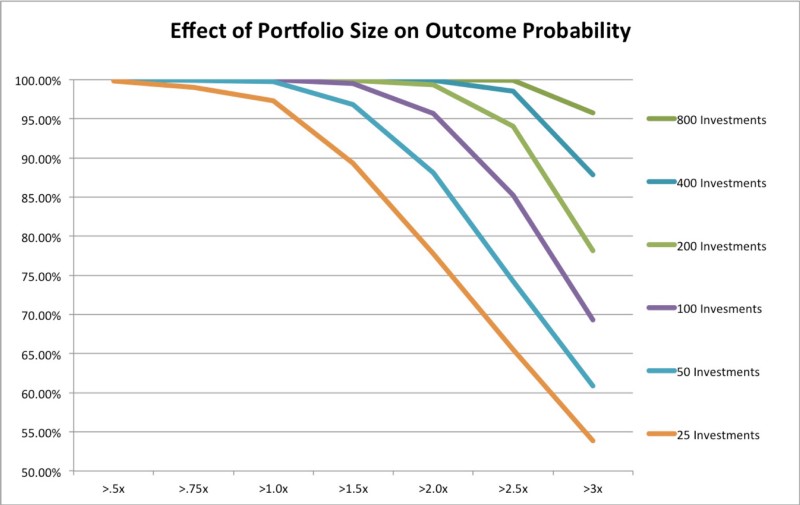

Regarding the first one, we’ve already touched on this at the top of the article. However, to bring it home, here’s an analysis from Kevin Dick of Right Side Capital.

According to the analysis, in order to have an 85 percent certainty of achieving its expected value, a startup portfolio must include 300 or more deals. To put it another way, if you are a typical VC and thus invest in about 10 new deals per year, it will take you 30 years to get to the long run. Until then, we won’t know if your results are a function of your skill or if you just got lucky.

In order to have an 85 percent certainty of achieving its expected value, a startup portfolio must include 300 or more deals. Tweet This Quote

Chris Sacca has the distinction of putting together perhaps the best performing single fund of all time. It includes Twitter, Uber, and Stripe, to name a few monster hits. But it should be obvious by now that with every new unicorn, there will be several prescient-seeming investors who got in early. And once in a while there will be investors who hit multiples, just like in poker.

Now you may be saying to yourself, “Yeah, but for an investor as well-known as Sacca to pick all these winners, it can’t be luck.” To which I would remind you that he wasn’t well-known when he picked them. He was just some unknown guy who was undoubtedly very skilled, and certainly very aggressive (see here and here). Plus, nobody can pick winners at the seed stage.

In both poker and VC there is a hot hand effect, which means that success breeds success. Tweet This Quote

I was at the WSOP in 2002 the year that Phil Ivey broke out into superstardom by winning three of the 35 events that year. Prior to that year, he was a great player, one of a handful of top young pros making waves. After that, he was seemingly invincible. Did his actual skill increase that much, or do people start treating him differently, making it easier for him to exploit his opponents’ weaknesses?

I would argue that in both poker and VC there is a hot hand effect, which means that success breeds success. In VC, if you get lucky and pick a unicorn, then not only do you have the bankroll to make unlimited more picks (thus increasing your odds of more unicorns), but you also get unlimited dealflow, and you don’t have to try very hard to get into any deal you want.

If my hypothesis is correct, then there are two things worth noting. First, being able to exploit the mystique in the way Ivey and Sacca do is a form of skill in and of itself. Second, the skill differential amongst VCs is not in the picking of winners, it’s being able to maximize the return on your investment if you happen to get lucky.

Every year, there are about 300,000 angel investors trying to pick the next unicorn. By the numbers, about 1 in 3,000 of them will do so. This will give them a bankroll and a “track record” with which to start their own fund and become the next Chris Sacca.

But, we will never know if they are good or just lucky. As they say in poker, the long run is longer than you think.

This post originally published on Medium