Global Issue

Illiteracy

Series

If You Can Read This

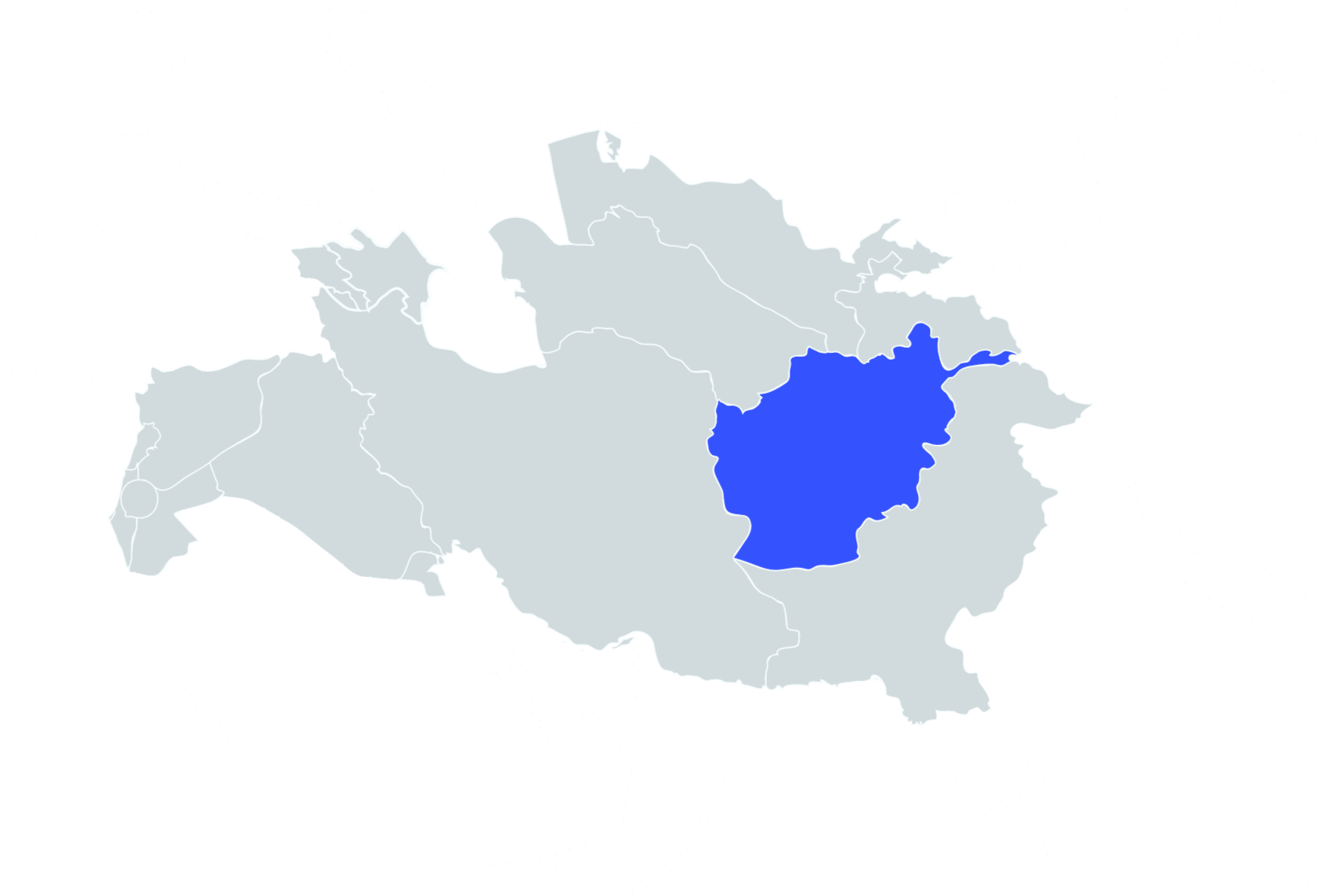

Last month, a U.S. government agency issued an assessment of the United States’ efforts to help Afghanistan recover from the devastation of 16 years of war. Its findings were grim. Six out of every 10 dollars since 2002 had been spent on Afghan defense forces, yet problems were rampant. Widespread illiteracy was found to be a “corrosive” challenge, undercutting progress not only in establishing security but also in carrying out civilian projects. The quality of leadership was also identified as a major stumbling block. “If leadership [in the defense force] is poor,” the author of the report said, “the people below don’t care, and they wonder why they have to die.”

At the root of the problem is the state of education. More than six out of every 10 people cannot read or write. Nearly four million children aren’t in school, and more than three quarters of all children drop out of school by the ninth grade. Overall, opportunity is extremely limited, making hope for the future impossible for many families to conjure. Not only does this lead to the significant obstacles to progress that the U.S. assessment points to, but it is also a situation that gives extremism and terrorism — and the warped meaning and sense of purpose it can provide — an evergreen appeal. Millions of Afghans, including children, are clear-eyed to the fact that their future is simply without hope.

Millions of Afghans, including children, are clear-eyed to the fact that their future is simply without hope.

The state of education in Afghanistan today actually represents progress compared to ten years ago, since there was virtually no ability to improve education during the many years my country was embroiled in war, starting with the Soviet Union’s 1978 invasion. Yet if we fail to make radical progress in our education system, the Afghan people’s ability to shape a more sophisticated economy, and a country in which war and terrorism are not tolerated, looks bleak.

Make no mistake — it is ultimately up to Afghans, not the U.S., and not the international community. While foreign aid dollars can provide meaningful support, local communities will ultimately have to produce and support the leaders of tomorrow who will help counter the twisted appeals of terrorist recruiters, fight to find ways for communities to prosper, and bring forth a future in which Afghanistan offers more of its people the promise of a better life for their children.

As Malala Yousufzai said, “I don’t want to kill terrorists. I want to educate the children of terrorists.” That is the true way to eradicate extremism in my country.

It is also why I launched Teach For Afghanistan, a program that is part of the Teach For All network and adapts the approach of Teach For America, here in Nangarhar Province along the Pakistani border, where 80 graduates from Afghan universities are teaching 23,000 girls and boys in 21 schools with the support of USAID and The Asia Foundation.

Afghanistan has the one of the youngest populations in the world and I believe that it could be our greatest asset. But too many who make it through our higher education system, or have the opportunity to study abroad, choose not to return to their homes to work for a better future for our country. Through Teach For Afghanistan, we provide a supportive pathway for young graduates to do so, while also helping to bring motivated new teachers into our overcrowded classrooms.

If our future is to improve, today’s children must learn to read. They must learn to write. They must learn to question dominant ways of thinking.

In 44 similar programs around the world, which include not just those well-known in the U.S., but in countries from India to Malaysia to Peru to Bulgaria, roughly 70 percent of young people who finish the programs stay committed to working to improve education for disadvantaged children in some way, even if they initially planned on following a completely different career path.

I’m hopeful that, over time, our program can help produce and inspire a new generation of collective leadership not just in communities in Nangarhar, but all across Afghanistan — leadership that is singularly committed to creating a future of opportunity and promise for each and every child.

Claiming that education is the answer might sound like a cliché, but it doesn’t make it any less true. If our future is to improve, today’s children must learn to read. They must learn to write. They must learn to question dominant ways of thinking. They must learn that no child is inherently worth more than another. If we can start down that journey today, we can all have hope for tomorrow.