In 2003, Naveed and Samiya Parvez gave birth to their son, Diamo. Medical negligence during birth led to cerebral palsy and severe developmental delay for Diamo, who required help with the most basic of functions, from sitting to eating. He wore several orthotics and braces to aid these daily functions.

However, it took series upon series of doctors appointments before the orthotics ever fit properly. Doctors would take measurements, send them off, and several months later, Diamo would receive the orthotics and braces he desperately needed. As a growing child, though, these products were destined to fail him. Naveed and Sam constantly questioned themselves: make it work, or go through the whole process again?

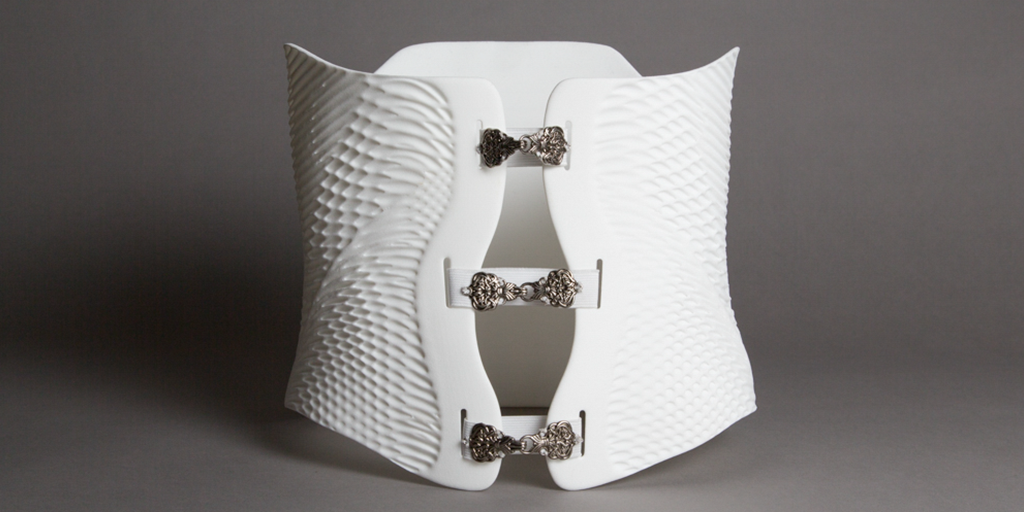

Tragically, Diamo passed away in March 2012. After their experience, Naveed and Sam were determined to figure out how to help other families avoid undergoing a similarly frustrating process. Using 3D scanning and printing, Andiamo delivers orthotics for children in a more human-centered approach to healthcare – in a matter of days.

We visited Sam and Naveed at their office in London to learn more about how they met, how they started this company with zero technical experience, and what kind of world they want to see through their work.

I would love to hear more about Diamo, to the extent that you’re comfortable sharing, because he’s so core to everything, of course. What about that experience led to Andiamo?

Sam: I’m originally from the Middle East, where disability is hidden. The most disabled person you would see is someone who’s in a wheelchair, but able to communicate and talk to you and do other things. So for me, Diamo was the very first disabled person I actually had an interaction with. I learned a lot, and he taught me a lot.

I think it’s taking that passion as a parent of, “I want to make sure that your life is as comfortable as possible,” and then multiplying it 10 times over with every single child who’s living the condition today – and knowing that we could make life more comfortable for the parents and kids as well.

Naveed: I think Diamo taught us to solve the right problem. It cuts through to what really matters, and the real problems sit behind the scenes. It doesn’t have to be scary, it doesn’t have to be painful, it doesn’t have to be distressing – it doesn’t need to be this way. And if we hadn’t been through that, then I don’t think we would actually understand that.

What happened to Diamo is the result of several physicians not intervening when they should have. How did that particular experience influence the work you’re doing now?

Naveed: When you look at what we went through, and you look at the transcript of all the things that went wrong, yeah there were a lot of humans that made mistakes. But those humans made mistakes because of the way the system is designed and run. It goes back to, what’s the real problem? And, we’ve been through it as a family. We’ve had to deal with the consequences of broken systems with so much of our time and energy.

Our friends and family just said, ‘If not you, then who?’ Tweet This Quote

It’s not about the fight with the people in the system, it’s about the system itself. It’s helping them understand that the care they can deliver could be so much better if there were things going on around them that could also change. That’s the conversation we try to have because we know they want to do better. There is no question that these people care about what they’re doing. It’s just they don’t go home with the consequences of those problems. It’s only when you start to bring the two back together that really significant and radical change can start to happen.

What did the system require you to do as parents of a disabled child?

Sam: We had a lot of medical appointments, mostly for orthotics, and they were all in different places. We had to go back over and over and over again for one particular thing because it wasn’t done right. If they didn’t get his back brace right, then he couldn’t sit up right on his wheelchair. He would collapse on himself, so feeding him was extremely difficult. It had a knock-on effect on his life, which had a knock-on effect on ours.

Because I had to go to multiple appointments, it was very difficult for me to actually work. So even though I had a temporary job on a contract base, I was taking time off every week. I’d have people looking at me saying, “But you’ve already been to that appointment.” And I had to explain that they get things wrong, which means I have to attend another one. This is life of a parent with a disabled child.

It’s not about the fight with the people in the system, it’s about the system itself. Tweet This Quote

What we wanted to end up with is you come once, you get your orthosis, and then you move on with your life. You don’t have to engage with us unless there’s something drastic that you want to communicate. We don’t want to see you again until your kid has actually outgrown it. Then, you come back for that one-hour appointment. This is where we want to get to, so people can just live their lives as families and not an extension of a hospital.

What does the system look like if it’s done right? What would be your vision of it, if it worked well?

Naveed: I think a system that works well moves away from a to-do list and a human as a list of symptoms. It gets back to having a genuine human-to-human interaction and understanding what they need, beyond just writing a prescription. When you make something efficient, you can also dehumanize things.

So how did the whole idea for Andiamo start?

Naveed: We had already been looking at finding technology for Diamo before he passed. We weren’t able to find anything before he did, and about a year later, I was invited to a conference. There was a guy talking about 3D scanning, using an old-world steam train to create a railway model.

He printed a replacement part for this train in one-to-one scale first in plastic, and I thought it was semi-interesting. But then they printed it in metal, and, that, like literally, light bulb moment. I just started asking everyone in my network, “Do we know anyone who’s doing this already within the National Health Service? Anyone doing this in medical, and if not, why not?”

The rest of the world shouldn’t be going through the same pain when you know you can change their lives for the better. Tweet This Quote

If you can do it for a steam train, why can’t we do it for wheelchairs? That night, I happened to sit down next to James [who ran the conference], and by that point, my idea was four hours old. I talked to him about Diamo, and he looked at me and he said, “I’m not going to let you leave until you promise that you’ll be able to make a prototype within a year.”

Still not quite sure why, but I agreed, and I went home at 1 a.m., blabbering on about lasers and trains and 3D printing and that we’re going to start a company. Our daughter was three weeks old at the time, and Sam was completely sleep deprived. A couple of weeks later, we had our first meeting in this building upstairs with James, and he literally emailed everyone he knew. A year to that day, we had two prototypes and a company.

Your background has nothing to do with tech or 3D printing. Why do it when you have no prior experience?

Sam: I think we’re more experienced in the pain. When things don’t work, your family life becomes so difficult because you live as if an extension of a hospital. This could be so easily fixed, and somebody should do something about it. That was our first driver. Knowledge would come with it, and the fight just started from there.

Naveed: The other thing we realized was that all the technical experts started in the middle. They didn’t experience the pain and the problems before you got to the technology, like living with that child, going to the hospital, doing all that day-to-day stuff. And, they didn’t live with the problem after the technology – going back home, things not fitting, things not working. Although it took us a little while, we realized actually understanding that was far more important than understanding the technology.

Throughout your research in starting the company, what did you uncover that told you that you needed to do something?

Sam: Every time we looked further into the 3D printing world, specifically in medical, there were one-off projects. Nobody was running a service. Nobody was thinking, “How can I use this and affect everyone around my community, my area, my country and maybe countries next door?”

From then, we were like, OK, we don’t just want to affect 1,000 people. The rest of the world shouldn’t be going through the same pain when you know you can change their lives for the better. That really drove us into thinking, how can we run this as a service, and what needs to happen to make it possible?

Naveed: We spoke to a lot of experts, clinicians, technical experts, and all sorts of different people. They were too focused on technology and had forgotten the humans they were supposed to be serving. Because we had lived it, we could bring an insight that they simply couldn’t and tackle a problem in a way that for them was impossible. And really, it was probably our friends and family who just said, “If not you, then who?”

What is the traditional process like for getting an orthotic?

Sam: The process of getting an orthosis can become very tiresome. The levels of anxiety go up, and it becomes very stressful for the parents and clinicians. For example, if you’re doing it for the ankle, you need to cover it in plaster of Paris and wait for it to dry. Basically, you pin down the child until it’s dry. Then, to remove it from the child’s limb, you’ve got to cut it. So they see the knife coming, and they think you’re going to cut off their legs. That goes away into the factories where they mold it, and then they put the plaster on it to create the actual ankle foot orthotic.

Worldwide, roughly about 100 million people and counting need orthotics every year. Tweet This Quote

Then, six months later – because that’s how long it takes – you’d get the child back into the clinic, and for the first time, the clinician and the parents would see this creation. And 9 out of 10, maybe 10 out of 10 times, it wouldn’t fit because the child is growing. So they would either have to change it a little bit, cut bits off, or add bits on. The parent would have to make a decision before going home: try and make another one and go through the whole process again, or just try to make it work because they just can’t wait another six months for it to be fixed again. It’s draining for the family.

Why does it take so long to make?

Naveed: It’s handmade, and there simply aren’t enough people to make it, so you’re put into a queue. The demand outstrips capacity by multiple factors. Then, you’ve got the secondary problem where, because you’ve created a situation where it doesn’t fit, you’re adding extra chaos to an overstressed system. You’ve got extra appointments and extra complaints. In theory, if there were enough people, you could probably do it in two weeks. But because of all these other inefficiencies, the wait times are only going to get longer, and the quality is only going to get worse.

So why is 3D printing better? How does it change the time and the length of the experience?

Naveed: 3D printing allows for three things. First, we’re able to digitally create something much faster in terms of using software. Then, the second thing is because it’s not a person physically making each one, we can print anywhere between 10 or 20 orthoses in one machine in one go. So you go from one person making one thing at a time to one machine making 20 things. The final thing is accuracy. When you’re hand-making stuff, your accuracy, realistically, is one to two centimeters. Our accuracy is 0.4 of a millimeter. So not only are we faster and more accurate, but we know it’s going to fit because we get it to the child within a couple of weeks.

Eighty percent of people who need orthotics live somewhere where they can’t afford or access the services. Tweet This Quote

And I know you can go to a family’s home as opposed to making the family visit your office. How does that improve the experience?

Sam: When you say to the family, “I’m coming to you, you just stay home and be comfortable,” that’s a huge weight off of their chests. They’re in a comfortable zone in an area where they feel safe and their kids feel safe. Just by doing that, you create a relationship with them.

Naveed: The other thing with being in someone’s home is the difference of healthcare being done to you, rather than with you. When it’s in your home, there is control. You’re not being dragged to yet another place. For a lot of these kids, traveling – even for half an hour – is massively distressing to them. So just by removing that from the equation, not only is it a more comfortable experience, but you’re also improving the outcomes.

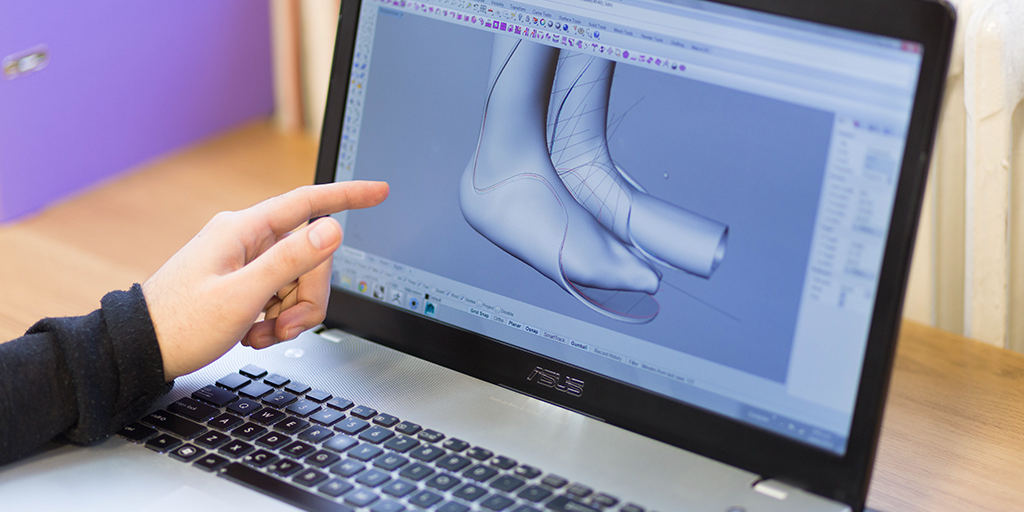

How does the 3D scanning and printing actually work?

Naveed: The scan takes 60-90 seconds, give or take. It’s not invasive; it’s just a light flashing on the limb. Then, we check the scan, and that gets taken to our designers, who then work with a clinician to design the orthosis. There’s a back and forth to sign it off, making sure it does what it’s supposed to do.

Then, it gets securely sent to one of our 3D printing partners. It gets put into their printer, and a cycle takes about 24 hours. Then, it’s shipped directly to us or whichever clinic I’ve been working at. We do some last minute finishing, like cutting straps, and then we fit and get immediate feedback. Most of the time, there’s no additions needed. And if we need to, because it’s all digital, we will just make changes to the digital file and redo the fitting.

To get a grasp of this issue, how many people around the world need this service?

Naveed: The number of people that need it in the UK is approximately 2.1 million per year. That’s growing by 6 percent compound annual growth. Worldwide, with very rough estimates, it’s at about 100 million per year, and that’s also growing. When we’ve looked at the studies, about 80 percent of those people are somewhere where they can’t afford or access the services that they need.

The other thing about the global aspect of the problem is there aren’t enough clinicians in our own developed health economies, let alone in other developing nations. When you start to look at the numbers you start to realize that we’re never going to catch up. We’re never going to train enough clinicians to solve this problem, so we’ve got to come up with other solutions.

It’s not that nobody cares; it’s that it’s so big, it’s so hard, and it’s easier to do other stuff. But this is actually such a simple solution that could help tens of millions of people, if not hundreds of millions. But it hasn’t had the focus and attention that other conditions have.

We’re never going to train enough clinicians to solve this problem, so we’ve got to come up with other solutions. Tweet This Quote

Entrepreneurship is hard, and health care is also a behemoth of a system. There’s an obvious personal reason, but what else gets you out of bed every day to keep on fighting?

Naveed: I’d say the thing that gets me out of bed is the realization that actually something quite small has this enormous impact in this child’s life. You’ve gone from a child who wasn’t walking very well or at all, to being able to do something like gymnastics, just because of quite a small intervention. How many other kids are out there that just need that extra bit of support to be able to do stuff they love?

And what I really, really hope is that some of what we’re able to do and some of the ideas we’re bringing will make people question, what else? Why not? Is it really that hard? That, I hope, is going to be the big legacy we leave behind.

What does success look like for Andiamo moving forward?

Naveed: That’s a good question. Success for us is quite a few things. Ultimately, it’s that the problem is fixed globally. We’re not in a position to fix the underlying conditions these children have, but we are in a position to make sure their lives are as comfortable, pain-free and joyful as they can be.

It’s not necessarily about it being Andiamo. It’s about, what does Andiamo enable others to do? Ultimately, when you’re talking about big, deep, broad, global problems, solving them requires local communities and people on the ground. It’s families. It’s clinicians who know these families that are going make this change. We can give them the tools and the knowledge, but ultimately it will be them.

This company participated in Unreasonable Impact created with Barclays, the world’s first multi-year partnership focused on scaling up entrepreneurial solutions that will help employ thousands while solving some of our most pressing societal challenges.