This post shares a four-minute clip from a conversation between Unreasonable mentor and former product lead at Google X, Tom Chi, and an Unreasonable Institute alumna entrepreneur. Tom shares a rapid prototyping framework to help solve for challenges related to distribution channels.

One of the most pressing issues facing many entrepreneurs in emerging markets is dealing with uncertainties related to distribution channels. In rural areas, there is often no official or reliable mechanism to ensure that suppliers will be paid back once their products are distributed.

One of the most pressing issues facing many entrepreneurs in emerging markets is figuring out distribution channels. Tweet This Quote

Rachel Starkey, founder of Transformation Textiles—a provider of affordable and reusable feminine hygiene products in rural Africa—was struggling with this in Kenya. With plenty of inventory, she was unsure how to best distribute it to her partner kiosks and guarantee financial returns.

By rapid-prototyping several experiments using a portion of their inventory, entrepreneurs can quickly learn how to master their particular distribution channels. Below is a simplified version of the process I recommended to Rachel, which can be adapted to a variety of contexts.

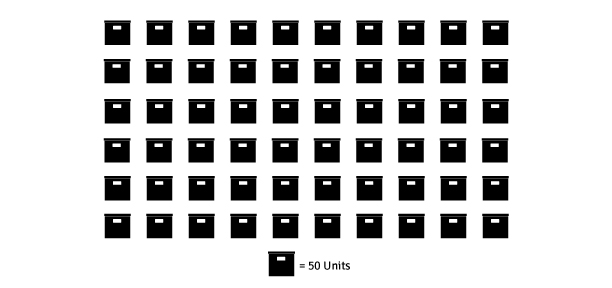

1. Partition the Inventory for Experimentation

In order to establish an example framework, assume there are 3,500 units of inventory. Turn the units of inventory into a bunch of separate experimental groups of 50 units each—enough units to supply a distribution channel like a kiosk for a few weeks, and enough groups to get reasonable data. Keep in mind that at this stage, it is important to try and pick inventory that is lower risk in value while still designing your experiments.

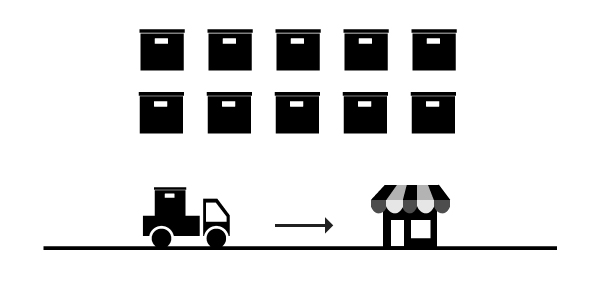

2. Create Your Experimental Frame

Say you choose to do 10 different experiments of 50 units each, using a total of 500 units of the 3,500 inventory. List and label the unique experiments. Each experiment will go to a different distributor, or kiosk in this case. Set a time frame, so you can come back to each experiment. In 4-6 weeks, for example, there’s been enough time for progress but not so long that a kiosk is out of the inventory.

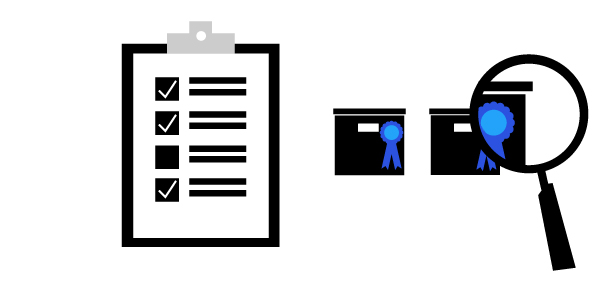

3. Record Your Learnings

Fast forward 12 weeks from the start of experimentation, once you’ve seen results. Perhaps 2 out of the 10 experiments produced favorable results. The kiosk owners paid back, and you understand the mechanism behind why they were more accountable. It might be a lot of different mechanisms. For example, it could simply be the personality of the kiosk owner or a co-signer who got on board and proved to be a reliable influence. What matters is taking note of what worked.

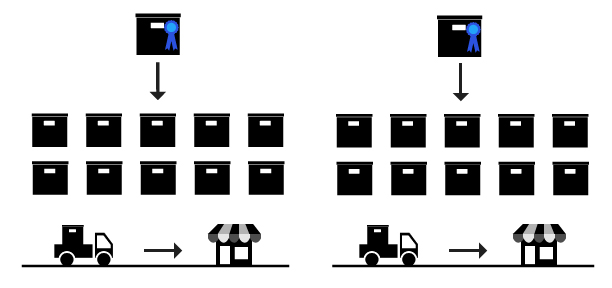

4. Optimize What’s Working with Further Tests

Select the two or so successful experiments and tweak them into a new round of 10 experiments, trying variations. For example, you could use the same incentive on a different kiosk owner. It might take 7 generations of 10 experiments each, but in most cases, it will probably just require 3 or 4 generations of systematic note-taking on what’s working or not in each generation. The early generations are likely focused around seeing if you get paid at all, and the later ones will be about optimizing what proved successful. This reflection and optimization allows you to best operationalize what was learned from scenarios in which you get paid, mitigating the risks of distribution.

For more information on rapid prototyping, check out this interview on UNREASONABLE.is and this TED talk about Google Glass.