With the republican party taking control of both the Senate and the House, their first act in power was to pass the Keystone XL pipeline. Now, the project rests in the hands of the President who said he would veto the project if it presented a serious risk of exacerbating climate change. If vetoed, Keystone XL would be the first big infrastructure project to be cancelled over climate risks.

Looking ahead to the 2015 Paris climate talks, many countries see Keystone XL as a test of whether America will actually walk the walk and not just talk the talk. Keystone XL would provide a cheaper transport route for oil from the Alberta tar sands, reducing the cost of tar sands oil. Cheaper tar sands oil means more of it would be extracted and burned.

Building a zero-emission economy will require educating leaders on the proven technologies Tweet This Quote

The impact from a large infrastructure project like Keystone XL embodies the type of thinking Steven Davis of UC Irvine and Robert Socolow of Princeton seek to change in a recently authored paper. Projects like Keystone XL have a much larger impact than their immediate emissions; Davis and Socolow want us to consider this total impact from day one.

Instead of counting carbon emissions as they billow from smoke stacks, Davis and Socolow’s method of measuring CO2 emissions, called “committed emissions accounting,” attributes the total lifetime emissions from oil, natural gas, and coal power plants to their first year of operation. Committed emissions accounting underscores that the investments we make today determine our impact in the future. With every fossil fuel plant built, the need for emission-free power generation becomes ever more urgent.

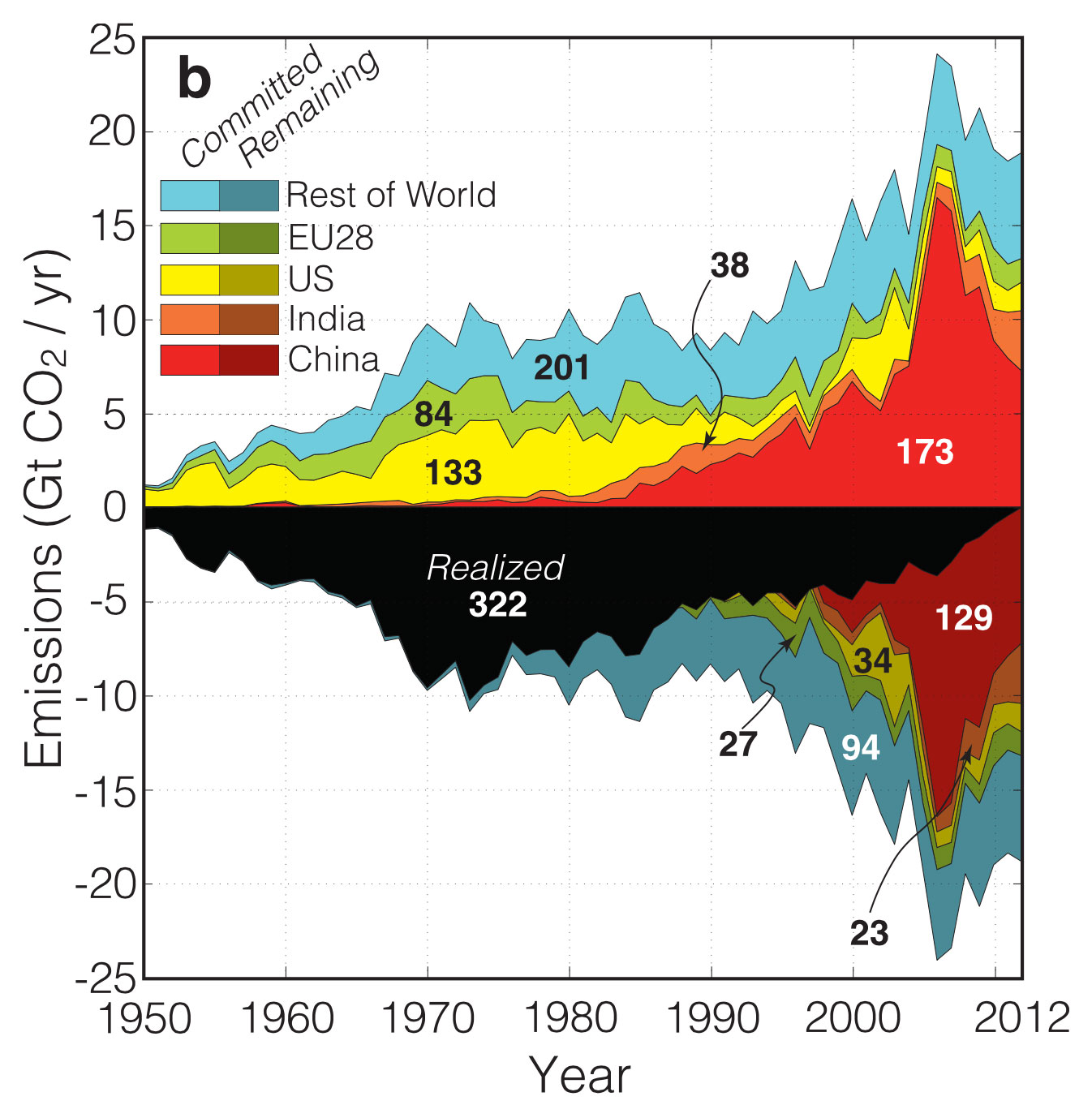

In 2011, the electricity sector produced 40 percent of global carbon emissions. Based on investments in fossil fuel electricity generators since 1950, 627 gigatons (Gt) of CO2 were committed. Of that total, 322 Gt have already been emitted, or realized, leaving 307 Gt of carbon emission remaining to be emitted over the next forty, or so, years.

Figure 1: Committed emissions for electricity generators. The numbers in white represent gigatons of CO2.

The graph from Davis and Socolow’s study illustrates how the main investors in fossil fuel infrastructure, and thus committed emissions, has transitioned from the US and Europe to China, India, and other developing countries. So far, China’s power infrastructure by itself has committed to emitting 129 Gt of CO2, or 42 percent of the total remaining commitments.

Investments in new fossil fuel generation are made simply because of inertia and not because they are the most cost effective solutions. Tweet This Quote

On the sunny side, the largest investors in fossil fuel generation are also becoming the biggest investors in renewable energy. Renewable technologies can provide cheap, zero-emission electricity. In fact, technologies with a proven track record like solar, wind, and energy efficiency are becoming a significant part of electricity generation by scaling to multi-billion dollar industries. Investments in renewable energy and renewable fuels totaled over $300 billion in 2014.

In 2013, China invested over $56 billion in renewable energy, more than all of Europe. Renewable power received more investment than new fossil fuel and nuclear capacity combined. China has ramped up both solar and wind power. In total, China has already installed nearly half of the 200 GW of wind power it has been planning for 2020.

India, under the leadership of the new Prime Minster, Narendra Modi, has taken a more serious position on deploying renewables as well. India recently passed laws making it easier for private and foreign investors to invest in renewable energy projects. These business friendly policies are meant to support India in reaching its recently announced goal of 100 GW of solar power by 2022.

As world leaders prepare for the 2015 climate summit in Paris, they must realize the world will be stuck with the infrastructure we build today until 2050 Tweet This Quote

Building a zero-emission economy will require educating leaders on the proven technologies that are already cost effective and the new business models that have been scaled up to reach the bold targets set by countries like India and China. Today, investments in new fossil fuel generation are made simply because of inertia and not because they are the most cost effective solutions. As Davis and Socolow demonstrate, each new investment in fossil fuel generation is a long-term commitment human society can’t afford to make. As world leaders prepare for the 2015 climate summit in Paris, they must realize the world will be stuck with the infrastructure we build today until 2050; they must opt for the cleaner, more affordable kind of energy: renewable energy.