When people talk about “innovation”, they usually mean new or improved technology. While technology usually forms the foundation of innovation, one crucial factor – namely the human one – is poorly understood in the overall equation. At its core, innovation is about the following three things: context, timing, and meeting some critical need.

As any tech VC will attest, timing is one of the key variables in determining the success or failure of any new innovation. But innovation either flourishes or flounders based upon the other two key criteria, too. While these are easy to identify, they are not so easy to understand. Below, I outline what it means and why it matters to understand the context and truly meet a critical need.

Fast Approaching Utopia, or Not?

At the present rate of technological innovation, one would assume the world is fast approaching a utopian state. By 2020, we could be living in a world where almost everything is of high-speed intelligent automation.

And yet, here we are, faced with many of the same problems of previous centuries: food shortages, competition for natural resources, destruction of the environment, inefficient resource distribution, wealth inequality, social instability, lack of education, lack of social mobility, and lack of communication. All of this at a time when we as a species are more connected to one another globally and at our most technologically advanced.

That said I believe humanity is being forced into a turning point. We simply cannot continue as we have without incurring dire environmental consequences. In my opinion, innovation is the answer to nearly every environmental challenge that humanity has or ever will face. There is nothing technology cannot or will not be able to conquer. Technology could save us, the planet and everything else. That is, of course, if we let it. And herein lies the conundrum.

That said I believe humanity is being forced into a turning point. We simply cannot continue as we have without incurring dire environmental consequences. In my opinion, innovation is the answer to nearly every environmental challenge that humanity has or ever will face. There is nothing technology cannot or will not be able to conquer. Technology could save us, the planet and everything else. That is, of course, if we let it. And herein lies the conundrum.

Innovation Dressed as Technology

Nearly every global company today cares about innovation, all with the intent of maintaining competitive advantage and remaining relevant. Undoubtedly, this is the right direction. However, when most companies talk of “innovation,” they really mean “technology.”

This leaves out one crucial element: the consumers or recipients of technology. In other words, the human variable in the equation is often ignored or at best poorly understood. Technology is the easy part – the human part, not so much. As Arthur M. Schlesinger wisely said, “Science and technology revolutionize our lives, but memory, tradition and myth frame our response.”

Today’s innovators are found primarily in startups (and increasingly within large corporations). Startups are great at taking risks to innovate because they have little to lose. However, they must compete with established business models, and changing accepted behavior is difficult at best.

Corporations, on the other hand, are great at mitigating risk and terrible at taking it. Traditional low-risk environments employ individuals that contribute to and thrive in firmly established corporate cultures. Type A personalities – the risk takers, the entrepreneurs, the visionaries – are generally marginalized in the consensus-driven world of the corporation.

Having an internal innovation program or working with various flavor-of-the-month startups does not guarantee forward momentum or success. Instead of attempting to understand consumers’ crucial needs and the context in which these needs arise, companies tend to focus on technology in and of itself as the answer. It is easier to understand technology than human behavior, after all.

Extrapolate this line of thinking onto society as a whole, and you begin to understand that regardless of the availability of technological solutions, adaptation and use may or may not happen. This is especially true if you have established profitable players in the market holding on to their market share by any means necessary.

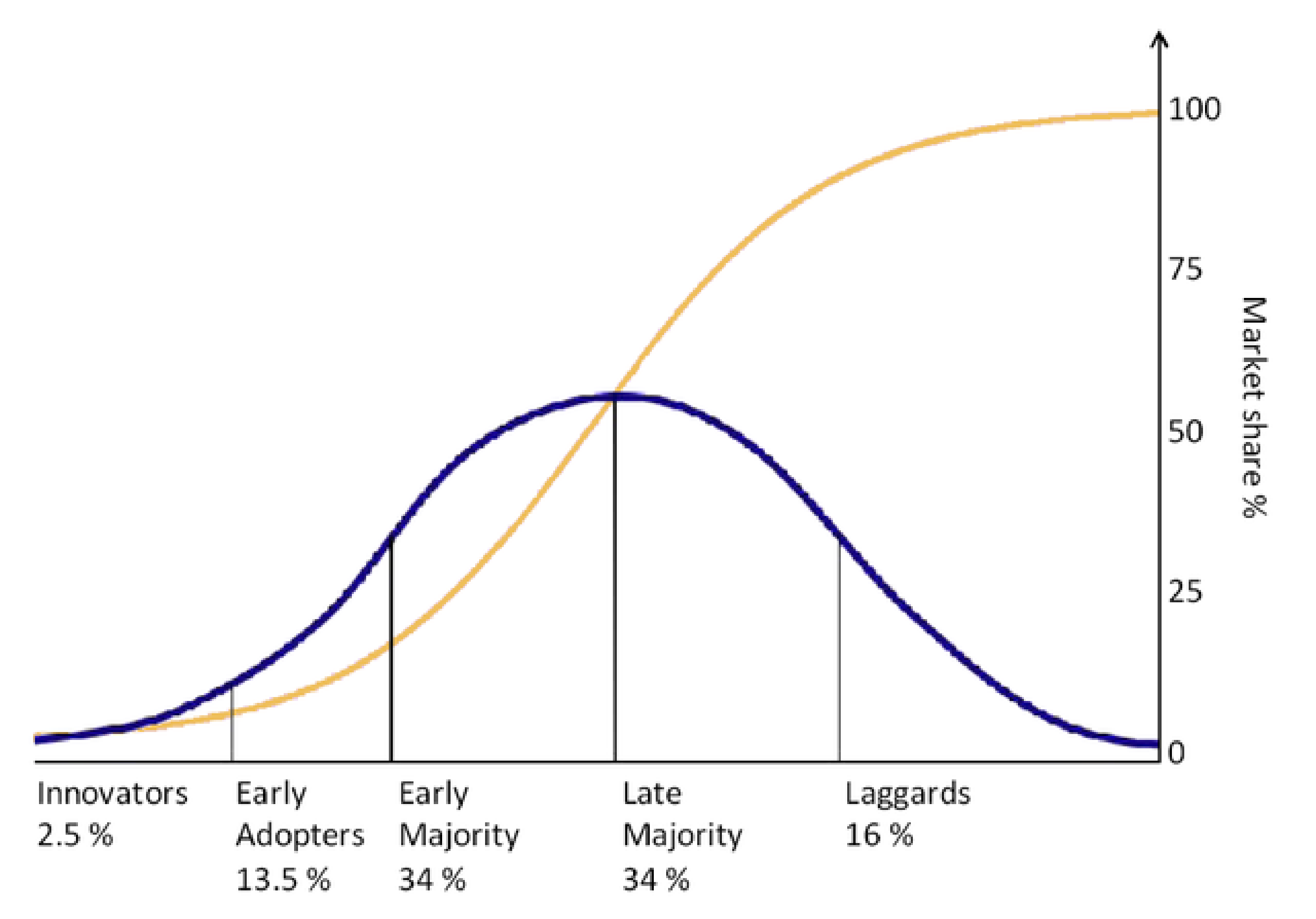

We know two things that help in understanding the general uptake of new technological innovations by society at large:

- The rate of uptake is happening faster today than it has in the past, and

- The uptake and use of anything new happens in stages.

However, this does not explain how or why any new innovation takes hold and becomes mainstream. What drives the introduction of disruptive change? Why take the risk if what you are doing now works well enough? Innovation is a nice buzzword, but understanding when, how, and in which context is the real challenge.

False Evidence Appearing Real (F.E.A.R.)

Most innovation these days is driven by the same force that drives much of human behavior – fear. Fear of being left behind, fear of missing out (FOMO), fear of becoming obsolete, and fear of losing business to competitors.

Fear has many names and faces. Fear has negative connotations, but by understanding that it is fundamental to our existence and born out of our need to evolve and progress, then fear makes for an awesome agent of change.

However, it seems as though fear drives a lot of the technological advancement without the needs-based assessment required for behavior to change with it. This is the fundamental issue at hand.

However, it seems as though fear drives a lot of the technological advancement without the needs-based assessment required for behavior to change with it. This is the fundamental issue at hand.

Innovation as Context

For the most part, the majority of people and companies resist change until they must. It is really that simple. The integration of a new technology or process becomes commonplace only when the alternative becomes impractical. Things change when they must, not simply because they can – unless, of course, you are an innovator or an early adopter.

Consider driverless cars. It is not just the technology behind the scenes that will determine its wide adoption. This technology already exists, and semi-autonomous driving cars have been around for a while for now. The answer to when driverless cars will become mainstream has many factors.

From the user perspective, the following considerations matter in determining the uptake of a driverless car: historical safety records, cost, current ownership of a traditional automobile, enjoyment of driving, physical location, alternative transportation, and family structure.

From the industry perspective, factors such as current non-driverless car sales, profit structures, the need to change existing manufacturing and logistics supply chains, changes in sales channels, speed to market, and competition are all valid variables.

From a larger societal perspective, the following conditions matter: the co-existence of driverless and non-driverless cars on the same roads, road condition and readiness, the shift from an ownership to a sharing economy, the democratization of travel, and the loss of social status (some people define themselves by what they drive).

The same can be said of any innovation adapted internally within a company or any innovation a company delivers to its customer base. Unless the context and the implications of the change are carefully considered, it will be met with varying degrees of resistance – regardless of whether or not the change is an obvious improvement. “Better” is generally irrelevant, or at least not enough to drive usage – something new startups too often fail to realize.

Must Have or Nice to Have?

Companies can innovate all they want, but unless a particular innovation is crucial to meeting a critical need, adoption and use will be slow and half-hearted. This is not to say that companies should not innovate, but they should do so with a comprehensive understanding of their limitations, the appetite and need for disruption, and their ability to deal with unpredictable consequences.

Most importantly, companies should innovate with intimate knowledge of their client base. Cost savings, speed, ease of use, accessibility and differentiation might not be enough to transform customer behavior. On the other hand, the absolute necessity to adapt or be left behind will.

In short, people, businesses, and societies change when they must and when many factors align – not because they want to. So while innovation is a worthy raison du jour, it only drives change in the right environment.

In short, people, businesses, and societies change when they must and when many factors align – not because they want to. So while innovation is a worthy raison du jour, it only drives change in the right environment.

Leave It Better Than You Found It

People and companies generally follow the path of least resistance. Real advantage lies in understanding the consequences of taking an alternative path. We can improve the condition for the vast majority of the world by safely abandoning our inertia and self-interest, and letting fear drive us toward rapid adaptation.

Keeping an eye on the bigger perspective, specifically that we all exist together on one planet, seems like the most basic of realizations necessary for our survival. Ultimately, this is why we must innovate and learn to adapt quickly – in order to leave the world a better place than we found it. Time is not on our side, but we have many of the answers already.