For the last decade, I’ve been designing solutions that improve human well-being in the developing world. For those who want to apply design thinking to situations of extreme constraints, like rural Cambodia, my iDE collaborator, Jose Mena, and I have some advice.

Use innovation to design experiences, not just things.

Don’t let your team settle for obvious solutions without understanding all of the stakeholders and the cultural or environmental conditions that underlie the problem. The most obvious solutions are products and communications campaigns. But sometimes people really need a new mode of service delivery, whether it’s a more nutritious street food vendor experience, or a business that will purchase the produce they grown on their farm.

At iDE we’ve learned that designing a service or experience can be a powerful tool to change behavior because it engages the audience directly in both the design and implementation. And that can lead to long-term impact. In contrast, a communications campaign will only go so far because people need to be coached on how to change. Products can be transformative, but they often require contextualized services to make them accessible, functional, and desirable. So don’t leave out experiences when you’re generating ideas for improving lives.

Use innovation, not only to disrupt a market, but to connect one.

In established markets, entrepreneurs deliberately look for new technologies that can disrupt the status quo. From digital music technologies to ride-sharing apps, consumers benefit from these disruptions with more choices and lower costs.

But in broken markets, which are the norm in developing countries like Cambodia, we need to create connections rather than cut out the middleman. The farmers who still irrigate by hand need access to pumps and lines. Rural families need a means to clean and store drinking water. Fixing these markets requires designers to answer the question: Why has the market failed these rural populations? The answer often involves re-introducing already existing market players who have mistakenly decided that there is no profit in serving rural populations. Our job is to design a business model that promises enough incentive to bring them into the market, and keep them there.

“I’m going to test my ‘right’ solution”

If you do a little research on the front end, you’ll avoid market testing the wrong idea. Research doesn’t have to be heavy-duty ethnography every time. It depends on the situation. It can be quantitative. Or it can be a lean startup methodology.

The important thing is to do some kind of investigation first, so you don’t finish a pilot or even a full-scale project before realizing that everything is wrong about it. And it’s cheaper to invest in a small amount of good upfront research first before committing to a solution that you only discover months or years later doesn’t work as intended.

You can’t innovate overnight.

It takes time to talk to people — it takes time just to get to the people you need to talk to. Once you’ve heard them, it takes time to process what you’ve heard, to brainstorm and generate ideas. Then it takes time to test and evaluate those solutions. Innovation shouldn’t stop when implementation begins. Program managers have to try out new ideas and measure the results — repeating that process throughout the life of a program.

The challenge is to keep the team focused on the innovation process that results in the most powerful transformation possible — walking that line between trying to do things quickly and doing things right.

Go where the findings take you.

People like to approach a problem with a ready-baked solution. Innovation, however, comes from uncertainty. To honestly engage in the design process, people have to be willing to take risks and to go where you cannot anticipate. This is a challenge to traditional project models, where planning has to be complete and then the plan must be followed with little deviation. Our best work comes from relationships with funders who understand that the process reveals solutions, rather than the opposite, and are willing to rework planning based on what we discover.

I find that the first time I go through the innovation process with a donor or NGO partner, they rely on trust in our past performance. Once they’ve made the innovation journey with us once, they understand the time, effort, and results, and often become evangelists for the process.

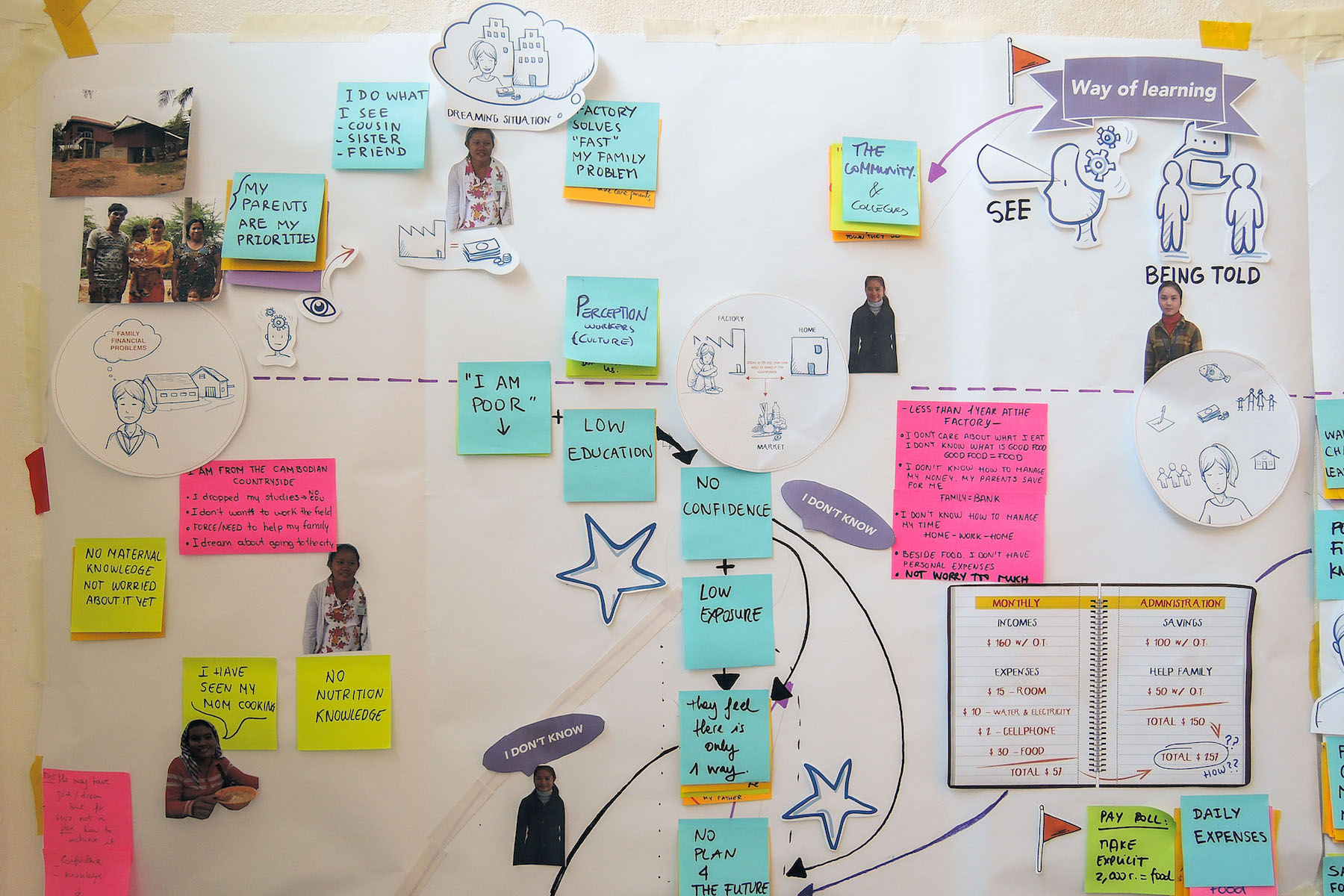

A recent problem we tackled: How can we improve the nutrition of young mothers who work in garment factories?

Working with CARE in Cambodia, we looked at a group of young mothers who worked in textile factories but suffered from chronic malnutrition. Without doing any research, you might assume that these young women didn’t understand nutrition and made poor food choices based on this lack of understanding. But as we began talking with them, and with the food vendors from which they purchased their lunches and snacks, we discovered that they were well aware of what food was more nutritious, they just couldn’t afford it and had no access to any other options. Meanwhile, the vendors didn’t want to spend more money to make their menu more nutritious.

INSIGHT: Before we could solve the nutrition problem of young mothers working 10-hour days in the garment factory, we first had to solve the food service problem. How can we influence street food providers to offer healthier options to their customers?

THE ANSWER: peer pressure.

We designed a contest experience with the new mothers as judges that pitted the vendors against each other to determine whose food was best. At the same time, we offered coaching to the food venders to increase their awareness of food hygiene, proper food preservation, and methods to improve food quality. In order to win the contest, the vendors would need to add better cuts of meat or more green, leafy vegetables.

This was just one of the solutions we developed, but I’m sharing it here because it’s a good example of innovation that goes beyond a product or a brochure. It’s a bigger idea that can lead to bigger impacts.

This was just one of the solutions we developed, but I’m sharing it here because it’s a good example of innovation that goes beyond a product or a brochure. It’s a bigger idea that can lead to bigger impacts.

Design innovation can be truly difficult, especially given the difficult constraints that underlie systemic problems like global poverty, but taking the time, effort, and cost in developing a new product, service, or experience can make the difference in people’s lives. That’s why it’s important and why we do it.

This article was originally published on Designorate.