In the past five years, Myanmar has cracked its once-locked shutters and opened for business.

The country’s road to reform has seen the power to rule transition from the hands of a brutal military junta, whose economic mismanagement crippled the nation and spurred widespread protests, toward those of a democratically-elected administration – led by Nobel Laureate and democracy advocate Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

It has also brought on a slew of foreign investment and interest (depositing Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurants and other foreign chains throughout the commercial capital, Yangon), surging mobile internet penetration rates, and even a promise from American president Barack Obama that sanctions against the country his administration still calls “Burma” will end.

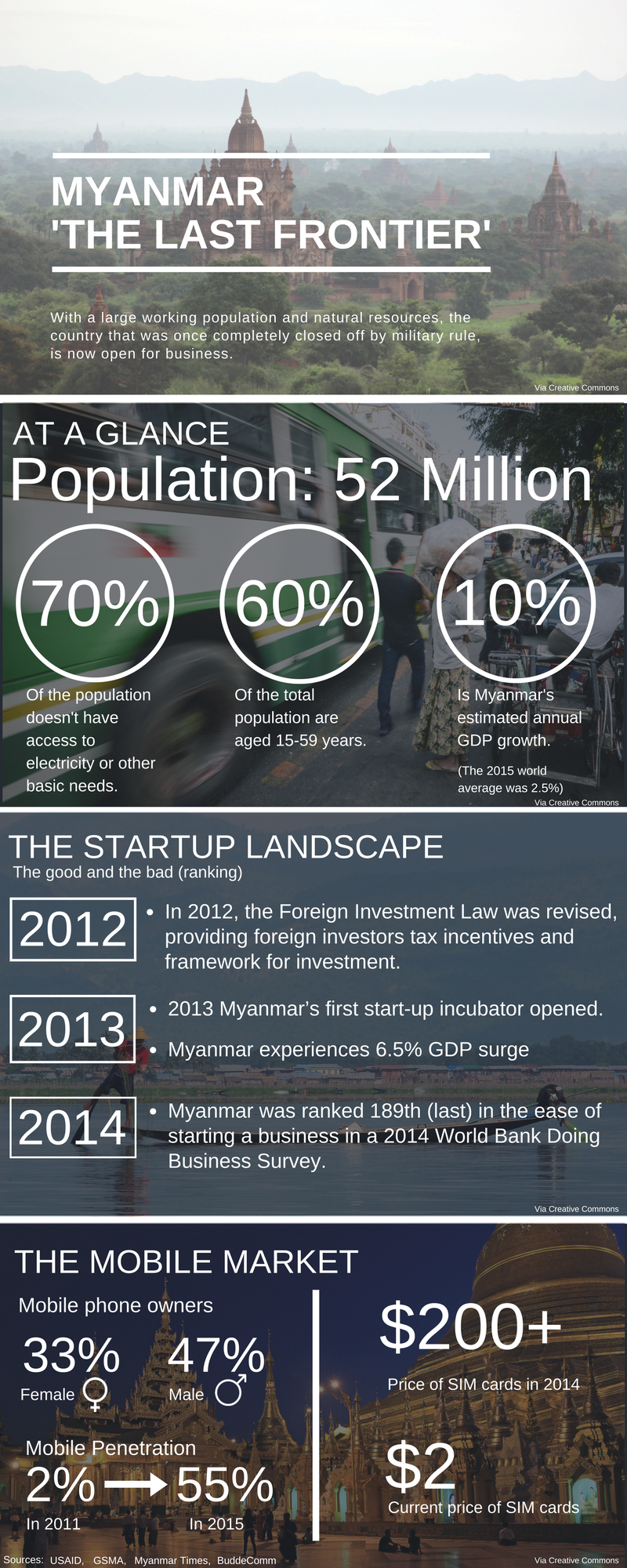

According to the World Bank, Myanmar used to be the hardest place in the world to start a business. Tweet This Quote

But that doesn’t mean entrepreneurs on the ground wanting to start successful businesses have an easy road. It’s a challenging one, quite literally, as the country struggles with a shaky infrastructure network and crippling traffic in Yangon. Though the opportunities to innovate seem endless, especially given the giant leap telecoms has taken in the past few years, the past still drags at the future.

“The whole connectivity revolution creates an amazing potential,” says Griffin Hotchkiss, a Yangon-based writer and aspiring entrepreneur. “The really optimistic viewpoint is to just look at the potential and not consider how handicapped you are in simple things like distribution and operations.”

Starting a business anywhere is difficult. But according to the World Bank Group, it used to be harder in Myanmar than any other place in the world for which data was collected.

However, Myanmar has simplified its incorporation process and gotten rid of minimum capital requirements for local firms, earning it the title of “most improved” in the category of starting a business last year.

Just five years ago, SIM cards could cost hundreds of dollars. Now, they cost less than $1.50. Tweet This Quote

And those weren’t the only changes in the past few years. According to Rita Nguyen, founder of retailer-focused technology company Jzoo, her phone and internet now work.

“I remember very distinctly that you always had to ask people, ‘Did you get my e-mail?’ Because they probably didn’t,” she says.

Just five years ago, SIM cards could cost hundreds of dollars. Now, they cost less than $1.50. And while in the past they were given out by lottery, now you can buy them on most street corners in downtown Yangon.

The liberalization of the country’s telecommunications sector has livened up the industry and vastly democratized access to the internet. Millions of people have gone online for the first time, and mobile penetration has shot up from 7 percent to almost 90 percent, according to one government official, though this claim may mislead as many mobile users in Myanmar have two SIMs cards or more.

Millions of people in Myanmar have gone online for the first time, and mobile penetration has shot up from 7 percent to 90 percent. Tweet This Quote

Meanwhile, electricity in Myanmar remains a major problem. Its main city, Yangon, is plagued by near-daily power outages and swaths of the country still have no access.

Its population is mostly unbanked as well. E-commerce payments are a hassle, and mobile money solutions are just now being introduced.

“Online payment systems are not widely used here in Myanmar yet, so we are creating an online platform while educating local people to [be] familiar with the digital ecosystem,” says Honey Mya Win, co-founder of an IT solutions startup called Technoholic. “We need the whole internet banking system to be working well and functioning.”

In the wake of Myanmar’s opening up and its connectivity overhaul, entrepreneurs have launched startups that deliver food, list jobs, and even hail cabs in taxi-choked Yangon. Yet, many techies and others had previously left Myanmar for education and better-paying jobs abroad.

Human resources remains a problem, one that will take a generation to fix, according to Nguyen. She also says that while more people are investing in Myanmar than previously, the conversations with investors are more difficult.

They’re not very interested in the market yet, according to one local startup founder, Thet Mon Aye, whose company, Ignite, provides a bus ticketing platform called Star Ticket.

Though Myanmar’s entrepreneurial landscape remains thick with stumbling blocks, it is also packed with opportunity. Tweet This Quote

“We are running so fast, but we need finance supporters,” she says over lunch in Yangon. “They think it’s very early for the Myanmar market, and the investment laws are not very sound as well, so that’s a problem.” Meanwhile, doing business in Myanmar can feel like playing a game with shifting rules.

“The unstructured business environment creates an unpredictable atmosphere for any business to operate,” relates Codeboratory leader Kaung Sitt. “From creating unscheduled appointments to high-value verbal deals done without a contract, doing business in Myanmar really depends on [the] mood of key decision makers, not the processes and policies. This creates both opportunities and challenges, but as we try to create a business environment for international investors, these will have to be changed.”

As Thet Mon Aye pointed out, startups rely on funding to give their ideas a go. Yet, unlike some other countries’ governments, Myanmar’s administration hasn’t gotten very involved in sponsoring innovation.

“It’s a very rough ride, to be honest, because we don’t have much support,” she says, adding that setting up a company in neighboring Thailand means obtaining government support and access to incubators and accelerators.

A new accelerator has just launched in downtown Yangon at a community tech hub called Phandeeyar, meaning “creation place” in Burmese. Its first cohort of six startups include Honey Mya Win’s, which aims to set up a platform where freelancers can find work, as well as others disrupting sectors from microfinance to tourism.

Though the country’s entrepreneurial landscape remains thick with stumbling blocks, it is also packed with opportunity.

“I think there are still many chances to grow, and there is a lot of help coming up as well,” says Thet Mon Aye. “If you want to do something in Myanmar, I think it’s a very good time because there are many projects to be done.”