This is the inaugural post of a series documenting entrepreneurship in East Africa and the companies that participated in the Unreasonable East Africa 2016 program.

In Uganda today, approximately 2.5 million children live with some form of developmental disability. Some of these children may be lucky to receive the care necessary to treat their conditions, but many of them will spend their days confined to a mat on the floor or bound to a chair, ignored or altogether disavowed by communities that are ill-equipped to address their needs.

Despite the Ugandan government signing and ratifying the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, 93 percent of the nation’s disabled children will never enter primary school. Without access to education or adequate health care, their futures look equally bleak: In northern Uganda, 80 percent of disabled people report living in chronic poverty.

Approximately 2.5 million Ugandan children live with some form of developmental disability. Tweet This Quote

Steve and Asha Williams, husband and wife co-founders of the Kyaninga Child Development Centre (KCDC), were living in Uganda when their son was born with epilepsy and a permanent developmental delay. In the year and a half following his birth, they traveled throughout Uganda and Kenya seeking support, and instead found only a critical absence of organizations positioned to help children with disabilities.

“The more we looked,” Steve recalls, “the more we realized how many kids needed help. These systems didn’t exist because most of the parents don’t talk about kids with disabilities. They think it’s witchcraft, or a curse, or judgment from God.”

Even when local governments run censuses, families often choose not to report disabled children.

“It’s not that families don’t care,” says Fiona Beckerlegge, KCDC’s third co-founder and chief therapist. “It’s that they don’t know how to.”

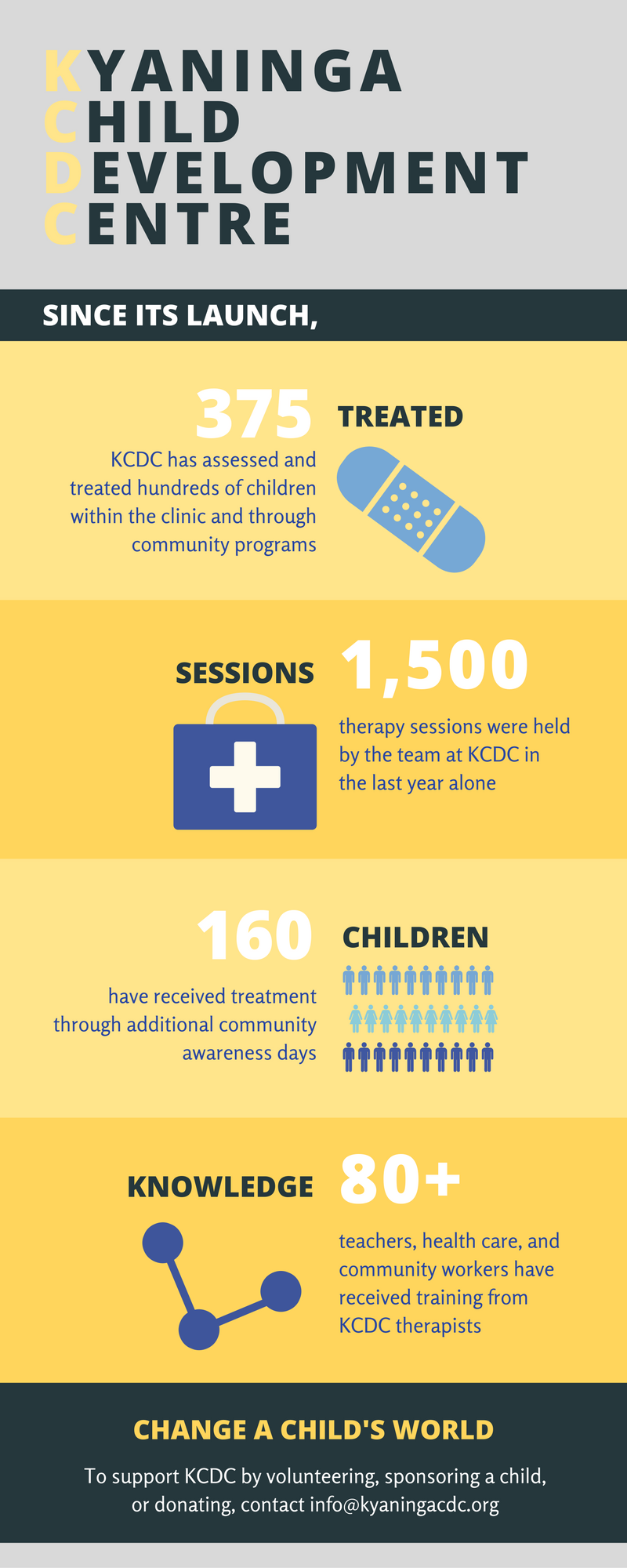

Beckerlegge moved to Uganda in October 2013 after responding to an ad for a physical therapist that Steve and Asha had posted in London following their son’s birth. Little more than a year later, the team opened KCDC in Fort Portal, in the Kabarole District of western Uganda. To date, the company is the only organization within 250 kilometers that provides multi-disciplinary rehabilitation for children with disabilities.

Most of the parents don’t talk about kids with disabilities. They think it’s witchcraft, or a curse, or judgment from God. Tweet This Quote

KCDC runs as an outpatient clinic that employs a team of Ugandan and British occupational, physical, and speech therapists, orthopedic officers, and community health workers. The staff also mobilizes every day in villages within 50 kilometers of Kabarole to visit homes, schools, and local health centers.

Of the children treated at KCDC, 40 percent live with cerebral palsy, a non-progressive brain injury that disrupts movement, muscle tone, speech, and varied aspects of development. A further 24 percent struggle with developmental delays that may not cause spasticity of the muscles, but which result from injuries sustained in birth or illness.

Infant mortality rates in Uganda have declined significantly since 2006, according to a report carried out by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics, but because mothers in labor often delay seeking medical attention, instances of birth-related disability have increased.

“What seems to have happened is that they’re saving more babies,” Beckerlegge says, “but those babies aren’t surviving without problems.”

Yet providing health and rehabilitation services for these children does little to address the larger attitudinal barriers that preclude them from fully realizing their rights as capable participants in their communities. KCDC therefore aims to dissolve the cultural stigma surrounding disability by raising awareness through community events and educating the children’s families about the viability of treatment.

“One of the most rewarding things for us is seeing the parents reconnecting with their children,” Beckerlegge notes. “We’ve had more than one mother say to us, ‘Thank you for giving my child back to me.’ Instead of seeing them as a burden, now the families are seeing them as a child again, and you can watch the relationships changing.”

Because mothers in labor often delay seeking medical attention, instances of birth-related disability have increased. Tweet This Quote

While KCDC does not currently charge for its services, the team may soon run trials in which community leaders motivate beneficiary families to pay a small fee that would enable the Centre to scale and serve more children. The challenges are then implicit: If a mother can’t afford to pay for her child’s medication, or in some cases, for the transportation to and from the clinic itself, how could she afford to pay a service fee? And if her child needs constant care at home, how would she manage to leave the house in order to earn wages?

To circumvent these limitations, KCDC equips families with the tools and skills they need to generate income from their homes. In addition to partnering with BeadforLife, an organization that provides business training and support to women in Uganda, KCDC also runs a closed-circuit produce program in which they gift goats to families and then buy back the cheese. In doing so, Beckerlegge explains, the team can create sustainable income for both the family and the company, which otherwise relies primarily on funds from a trust set up in the U.K.

Looking ahead, KCDC plans to expand its community outreach program and to establish a second Centre in Kabarole’s neighboring district. Within the next year, Steve also hopes to open a third operation in Kampala, where the company could charge more for services in order to sustain its rural branches.

‘Instead of seeing them as a burden, now the families are seeing them as a child again.’ Tweet This Quote

In the meantime, the team continues to build community awareness in an effort to foster the reintegration of disabled children into society.

“We are now really trying to find ways for the children to be given a chance to go back into elementary education,” Steve says. “We’re speaking with teachers at schools that lack specialist programs and seeing what adaptions could be made on the child’s behalf. Many of them are now agreeing to allow us to follow up and provide training.”

The Centre will also soon host several events — from a professional ballroom dancing competition to an inclusive sports day in partnership with the Ugandan Special Olympics Committee — that will encourage awareness on a larger scale.

“We’re hoping these events will draw a lot of people so that we can use them as an opportunity to get the culture to accept the children more,” says Steve. “When communities turn up, see that the child matters, and people actually believe in him or her, it has a very, very big impact.”