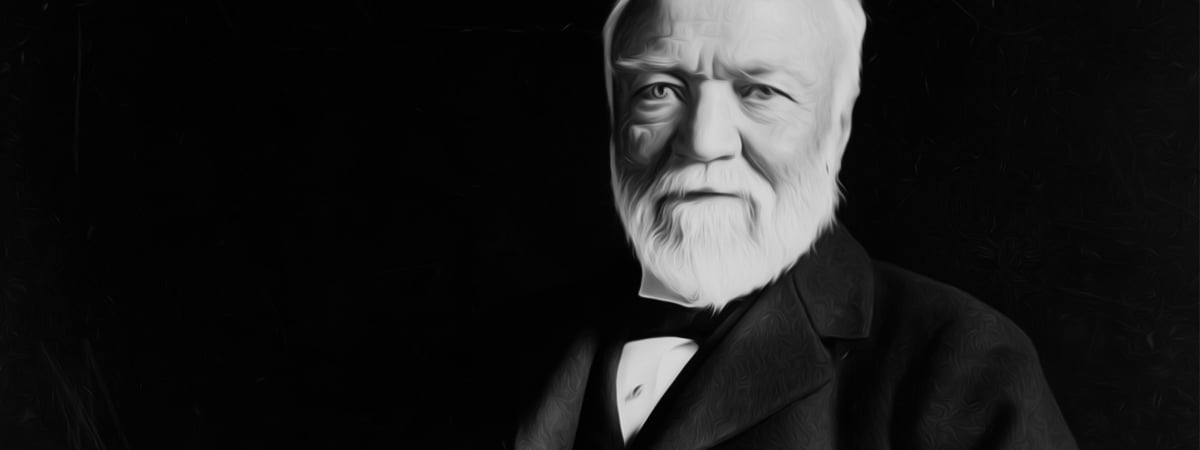

Most people follow a century-old paradigm of philanthropy, popularized by Andrew Carnegie back at the turn of the 20th Century. Simply put, maximize the return of investments, and give a portion of those earning to charity.

In Carnegie’s case, those investments provided him so much wealth, that despite giving away an equivalent of $5 billion in his two decades as philanthropist, enough of his wealth remained that 100 years later two foundations, the Carnegie Corporation of New York and Carnegie UK Trust are still up and running, with more than $1 billion in endowments.

Hundreds of other wealthy entrepreneurs have since followed this same model, with Bill Gates and Warren Buffet being the two biggest philanthropists this decade, promising to give away most of their combined $100+ billion in wealth. The question I and others have starting asking is whether there is another way. Whether it is possible to combined the social good of philanthropy within the act of doing business? And specifically for investors, a question of whether it is possible to do good, while providing a reasonable return on investment.

To answer this question, we need to understand how investing and philanthropy are related. To do this, let’s create a “magic square”, placing investing in one corner, and philanthropy in the other.

To connect these concepts we need two common measures. On the vertical axis, we have “return on investment”. For traditional investing, the goal is to maximize the return. For philanthropy, the expectation is that there will be no return (beyond the proverbial PBS tote bag). On the horizontal axis, we have “impact”, as in a positive, measurable, social or environmental impact. The point of philanthropy is to have an impact, and thus the high impact is on the right, whereas traditional investing does not include a measure of impact.

The result is a landscape that explains the differences between the goals of investing and philanthropy, but which still contains a large gap between the two. However, with this landscape, understanding that each axis is a continuum of values, a new important question arises… what does it mean to be a point within all the empty space between the two labeled corners?

Let’s look at three investments that fit into that space: Whole Foods, Ben & Jerry’s, and Zipcar. All three are mission-driven companies, aiming for a positive impact as well as profits, hence they fall on the right side of the landscape. All three were good investments for their initial shareholders, with Whole Foods having a successful IPO, Ben & Jerry’s being acquired by Unilever, and Zipcar acquired by Avis. Hence they are at or near the top of the landscape.

We can quibble over where specifically these companies should be plotted on the landscape, but given their missions, they certainly deserve to be placed somewhere different than Exxon, Philip Morris, Kraft, Pfizer, Apple, or Google, whose missions are maximizing shareholder value, no differently than Carnegie’s U.S. Steel or Rockefeller’s Standard Oil or Gates’ Microsoft.

More importantly, with these three small examples, we can realize that there are a whole host of valid options for investments within the landscape between traditional investing and philanthropy. This is an area that is being called “impact investing.”

There are a whole host of valid options for investments within the landscape between traditional investing and philanthropy. This is an area that is being called “impact investing.”

As the landscape shows, impact investing covers a broad swath of potential investments. It includes socially responsible investing (SRI), divesting your portfolio of tobacco, oil, and other such “harmful” stocks. At the other end of the landscape it includes microlending sites like Kiva.org, where you can lend an entrepreneur $25 or more with no interest, but with your the return of your original capital. And in-between, it includes the top-left quadrant of profit-driven companies that aim to do some good in the world; the bottom-right quadrant of mission-driven companies that aim to run via customer revenues, not philanthropy; and the top-right quadrant which achieve the best of both worlds, doing good in the world while returning a market-rate return.

With this new paradigm of all money having an impact, imagine how much more “good” could be done. Tweet This Quote

With this landscape, and the investment options therein, new strategies emerge that make no sense when investing and philanthropy are two separate activities. For example, in foundations, where 90% of the funding sits in the safety of S&P 500, Treasuries, etc., 5% is invested speculatively, and only 5% given away to fulfill the mission of the organization, impact investing can be used to empower all 100% of the dollars toward impact. For high-net-worth individuals, the same is true for their “nest egg”, today locked away in mutual funds, hedge funds and a mix of bonds that together aim to “beat the market”, so that the nest egg grows while perhaps 10% of those gains are given away to charity. Instead, all 100% could be focused on impact, mixing SRI for the core investments, with sustainable forestry, green building, community trusts, and other impactful investments mixed in.

With this new paradigm of all money having an impact, imagine how much more “good” could be done.

“Conscious” businesses, doing good while doing business, side-by-side with philanthropic organizations, doing good where there is no business to be had.