Surviving centuries under a dominant culture of colonial imposition and manifest destiny has left its scars on the Mohawk Nation and has created an unwanted legacy of fighting for clean water and land. Local communities continually face a cyclical conflict when it comes to decisions based on their energy needs and the contradictory effects these decisions have on the environment.

The Mohawk Nation faces a cyclical conflict when it comes to decisions based on their energy needs.

The Mohawk community of Akwesasne, which straddles the international border of the United States and Canada, now faces such a dilemma and will soon decide if they will move forward in a mutual venture with Enbridge Gas Distribution. This deal will provide the residents of a small portion of the reservation with access to natural gas via an expanded pipeline as a cheaper alternative to fuel oil.

Compounded with the moral, environmental, and financial interests of stakeholders, these situations often result in controversies as the short-term financial benefits to the community compete with the potential long-term detriments.

The Akwesasne Mohawk Nation straddles the U.S. and Canadian border and covers territory in New York, Ontario, and Quebec. Photo: Michel Rathwell.

Keepers of the Eastern Door

Home to around 12,000 Akwesasne Mohawks, commonly referred to as Akwesasronon (pronounced Ah-gwey-sahs-loo-noon), the international Akwesasne Mohawk Territory has had its fill of fighting for environmental justice against corporate pollution and has a long history of exposure to the dangerous chemicals from upstream companies like Alcoa, Reynolds, General Motors, and a paper mill.

The actions of these companies have resulted in decades of water pollution which has led to widespread land degradation issues and negatively impacted the cultural, emotional, environmental, social, and physical well-being of the Mohawk people.

For some time, it was advised to avoid even touching the water or using the land in many areas.

To this day, the region is still fighting to recover from these often unnoticed atrocities. Its people have endured many forms of cancers and illnesses, and have sacrificed their ability to eat fish or use plants that grow in the St. Lawrence River and the many tributaries that surround the Nation. For some time, it was advised to avoid even touching the water or using the land in many areas.

The Akwesasne Mohawk Territory is one of several Mohawk Territories situated in Ontario, Quebec, and New York. The Mohawk Nation is also one of the six brother nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, which spans predominantly across modern-day New York and Ontario, and are considered to be the first defense for the “eastern door” of the Confederacy.

Because the Nation is situated on the border of two countries, the community is made up of two different types of Band members. Individuals can be enrolled through the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne (MCA) on the Canadian side, or through the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe (SRMT) on the American side, or both.

With a unique border to the Territory, the Akwesasronon have adjusted to federal, state, and provincial jurisdiction issues that relate to Canada, the United States, New York, Ontario, and Quebec. Despite these variable laws and corporate neighbors in surrounding areas, this unique indigenous community has had to fight for autonomy and survival from diverse outside influences.

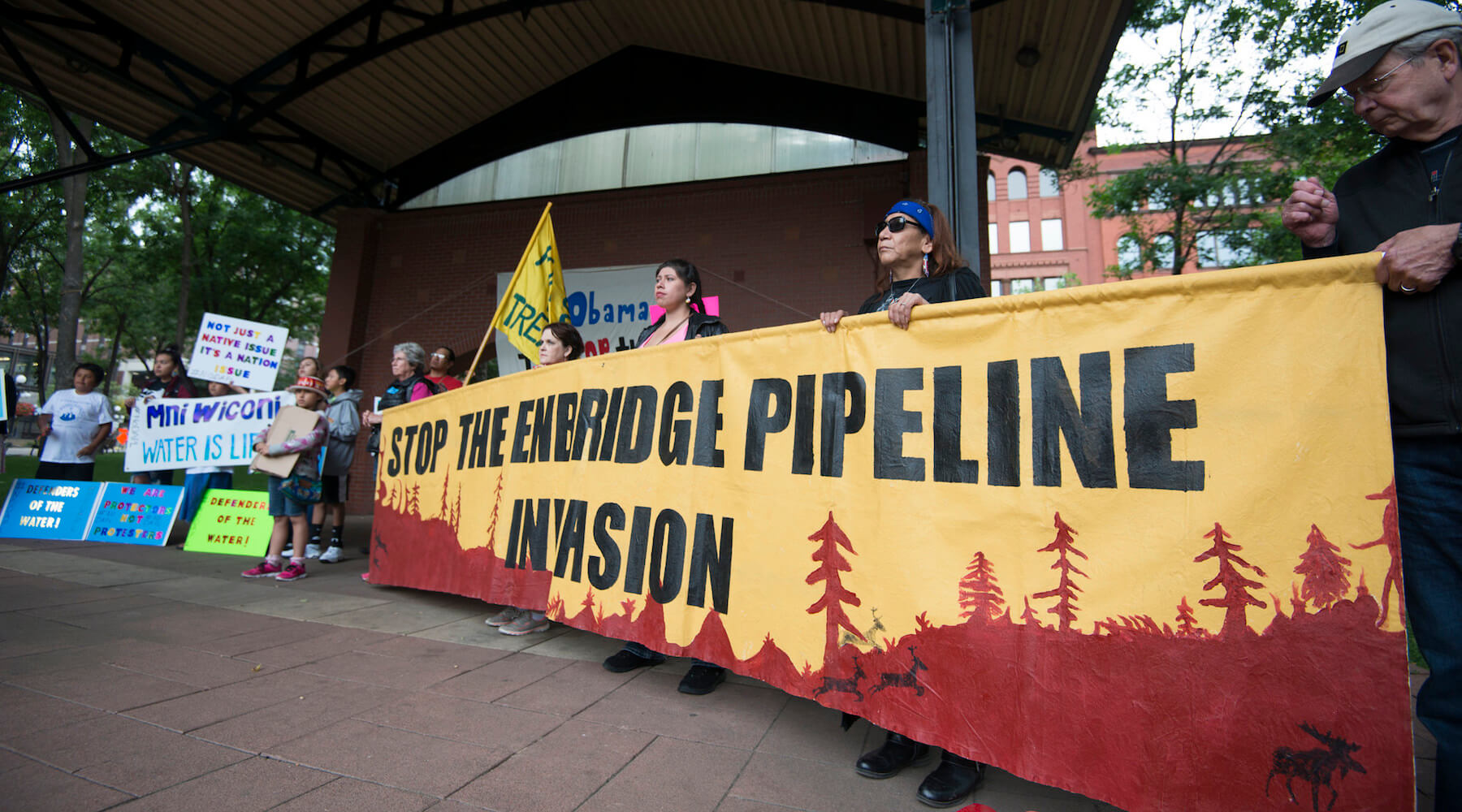

Enbridge Gas Distribution faced the same opposition to their pipelines in 2016 as one of the major companies involved in the Standing Rock Sioux conflict. Photo: Fibonacci Blue.

Echoes of Standing Rock

The relationship between the Akwesasne Mohawks and Enbridge Gas Distribution is deeply rooted in a history of tension. The Mohawk community on Cornwall Island have been associated with Enbridge, one of the many oil and gas companies involved in the 2016 Standing Rock Sioux conflict, since 1962, when an original pipeline was built through their land in order to service Alcoa in Massena, New York. However, after many years of negotiations, it was not until 2009 that they were finally compensated and acknowledged for historical land use and right-of-way.

There is now a stark internal divide between residents who support increased access to natural gas as a cheaper alternative to fuel oils, and those who oppose further collaboration with Enbridge.

In late 2011, Enbridge was forced to relocate their original pipeline in conjunction with the demolition of the North Channel Bridge, and a new 12-inch pipeline was created in order to go under the St. Lawrence River rather than across it. This project sparked an interest for Enbridge to not only relocate their pipeline but to also expand it.

Both the MCA and the SRMT agreed to consider opening the Akwesasne Mohawk Territory to this proposed expansion, which included the possible construction of a transfer station on Cornwall Island that would connect the existing pipeline to potential new distribution lines. There is now a stark internal divide between residents who support increased access to natural gas as a cheaper alternative to fuel oils, and those who oppose further collaboration with Enbridge.

This became especially apparent when Enbridge was allowed to engage in subtle public relations endeavors, such as scholarships, annual donations, and sponsorships of public events, which clearly show corporate efforts to ingratiate themselves with potential new natural gas consumers. Fueled with emotion and unease, members of the Akwesasne Mohawk Territory voiced their concerns to the elected Chiefs about furthering their community’s relationship with a corporation that has an arguably violent and anti-sustainable history.

At a recent meeting in May 2018, one anxious resident made it clear that this is not just a decision about saving money during cold winters, “Here you are supporting the same company that sends dogs and tear gases our people…. You guys are supporting this company. Where do we stand? I just want to know.”

The destruction and replacement of the North Channel Bridge, also referred to as the Cornwall Bridge, presented Enbridge with the opportunity to not only replace their existing pipeline but also to expand it. Photo: Michel Rathwell.

A Catch-22 for the First Nations’ Footprint

In the same MCA general meeting in May 2018, some shared statistics asserted that a transition from fuel oils to natural gas as heat fuel would instantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50 percent for residents, causing a massive decrease in the overall carbon footprint of Akwesasne.

The switch to natural gas is a short-term solution that benefits the purse and not necessarily the planet.

This topic is of great interest to the Canadian government, which is committed to taking actions that reduce greenhouse emissions, and the Ontario government is offering billions of dollars to First Nations for environmental conservation projects that can produce a smaller carbon footprint.

The immediate decrease in greenhouse gas emissions is definitely an improvement and a move in a sustainable direction, but the switch to natural gas is a short-term solution that benefits the purse and not necessarily the planet.

Natural gas is a nonrenewable resource, and requires a production process in which methane (a top greenhouse gas) is often leaked and released into the air. Drilling can cause earthquakes that destroy useful land, and the use of hydrofracking can pollute and/or overuse water sources. Moreover, natural gas still produces greenhouse gas emissions because it is a combustible fuel. It is also a short-term solution that may not consider the potential increase in international demand. An increase in use means an increase in emissions and the eventual need to drill new wells in new places.

With the Canadian government’s focus on reducing greenhouse emissions, the switch to natural gas is an appealing proposition. For many Akwesasronon, however, it seems like a short-sighted solution. Photo: Michel Rathwell.

Approaching the Decision

As the seasons prepare to shift, residents begin to think of the extreme, prolonged cold that likely lies ahead. Some Akwesasne residents on both sides of the border are conflicted about the desire for lower heating bills, the moral dilemma that accompanies a deal with Enbridge, and the environmental degradation that comes from natural gas production and consumption.

With the intent to increase public awareness and deepen the community’s understanding about natural gas as a resource, MCA Grand Chief Abram Benedict confirmed that a four month-long information dissemination process has begun in order to provide residents with more information.

Some concerned Akwesasronon have taken it upon themselves to offer everyone in the community an open, safe space for dialogue on this issue.

This information process is to be completed before the next public interest survey about the pipeline is prepared. The upcoming survey will be conducted door-to-door to ensure high participation, however, it wasn’t clear what questions would be asked, what quantitative data will provide the results needed to greenlight the proposal, or if the survey writers have formal experience with statistics. It is also not clear if the survey will lead to a final decision about accepting the deal with Enbridge or if the residents will be offered a referendum to vote upon. Grand Chief Benedict did affirm that the survey would be written by MCA staff and that it would not include any input or influence from Enbridge.

While the MCA determines if the residents of Cornwall Island or the Akwesasne Mohawk community at large will have the final approval power for the Enbridge proposal, some concerned Akwesasronon have taken it upon themselves to offer everyone in the community an open, safe space for dialogue on this issue.

In an informal gathering, referred to as the Unity Fire, members have the opportunity to share what they know about the proposal and to create peaceful solidarity against corporate influence on their home territory.

The Unity Fire is a continuation of the fight against corporate interests in First Nation communities, where people come together to share stories and ideas, disseminate information about community meetings, and to empower each other as Onkwehonwe (the Original People) in the ongoing struggles for self-sustainability. The gathering is a peaceful initiative to form a collective mindset of continued sovereignty and solidarity in the face of international corporate influence.

The Ability to Survive

While the land, waters, and people recover from previous decades of upstream corporate pollution, the Akwesasronon are, in many ways, thriving. They boast a wide range of businesses and services such as environmental departments, assistance programs for Elders, and many health and wellness programs on both sides of the territory.

In fact, The MCA has an impressive range of environmental conservation and innovative plans, including two alternative options to the Enbridge pipeline that were presented by James Ransom, former director of the Department of Tehotiiennawakon (translated to mean “They Work Together”) at the general meeting in May.

The first option is potential investments in a successful wind turbine company that would bring in revenue and cheaper electricity to residents, while the second is an energy conservation program that will begin to retrofit and upgrade 1,000 homes over the next four years with new windows, energy efficient furnaces and appliances, and re-insulated basements.

This territory of people has been under frequent corporate attack for the last decade, and yet they have found a way to make their voice heard to try and maintain their way of life — a vitality worthy of mention.

The question, then, of the community’s resilience in response to yet another corporate invasion remains to be answered.

“The resilience of the Mohawk people with their ability to survive over the past few centuries should be applauded,” said Jake Swamp, the late Mohawk Faithkeeper. “When we look back on our past history we can appreciate the accomplishments of our ancestors as well as the hardships they faced to maintain who we are. Two hundred years later we’re still here, together, as a community and nation trying to overcome the problems of today.”

The question, then, of the community’s resilience in response to yet another corporate invasion remains to be answered. While Grand Chief Benedict has affirmed throughout this process that the power to make a decision remains with the residents, his response when this affirmation was called into question was less than convincing.

“Council is still deciding on how to handle whether the community or residents will decide,” he said. “I believe all of the community has a voice and should be considered.”

In the meantime, hopes are high among many Akwesasronon that the eastern door will close on any deal with Enbridge, and with it, a longstanding history of corporate exploitation and unbalanced compromises that result in questionable benefit to the Mohawk community.