This post is part of a series documenting entrepreneurship in Mexico and the companies that participated in the Unreasonable Mexico 2016 program.

Gabriela Calderón and Nancy Otero were graduate students at Stanford when they discovered that they shared a common frustration with the education system and lack of innovation in Mexico. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) assessment scale, student performance in Mexico is low compared to other countries, and 25 percent of 15 to 29 year-olds are not in education or not employed.

Being a country that traditionally specialized in assembly and manufacturing, Mexico doesn’t place much emphasis on teaching innovation and problem-solving skills. In our increasingly entrepreneurial global economy, Calderón believes this is a reason why Mexico’s per capita GDP growth has been volatile, and averaging at an average rate of one percent in the last two decades.

The only way to generate greater added value is by educating people to innovate and to be internationally competitive. Tweet This Quote

“We know that in order to construct a solid economy, it needs more design and innovation,” Calderón explains. “The only way to generate greater added value is by educating people to innovate and to be internationally competitive.”

When Otero took a class on Digital Fabrication and learned about the maker movement, things started falling into place. Her professor, Paulo Blikstein, is also Director of FabLearn, an organization that creates “fablab@school,” or workshop spaces for digital fabrication for education – often involving tools like a 3D printer and laser cutters. Once Otero explained the FabLearn concept to Calderón, they knew they had found their solution to bringing design and innovation to education in Mexico.

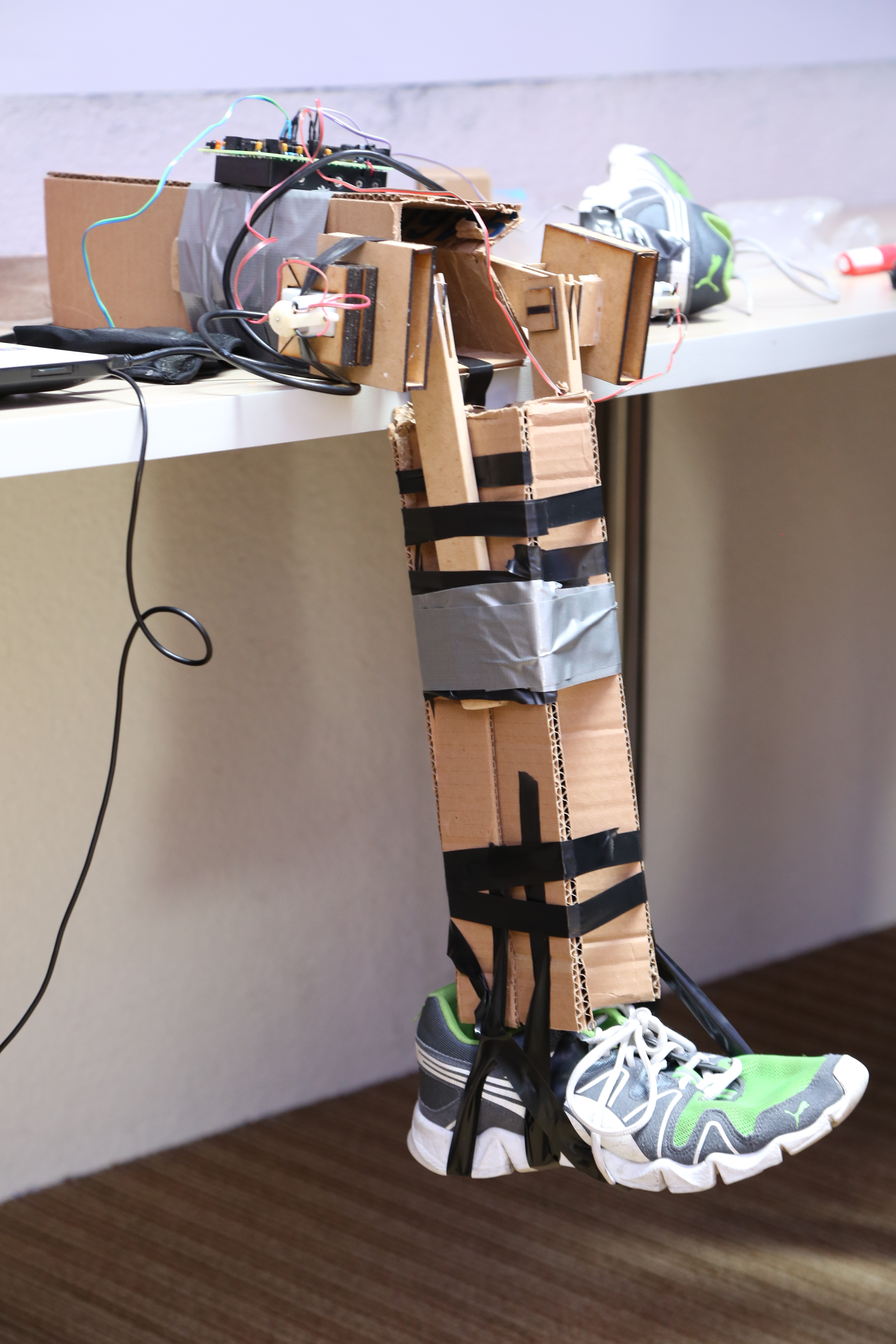

A prototype constructed during one of the workshops. Photo courtesy of FAB!

With Blikstein’s blessing, Calderón and Otero approached a university in Mexico City called the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education (TEC). On board as official collaborators, TEC lent Calderón and Otero a workspace, 3D printer, and laser cutter. The duo then invited students from a local public high school, and using the FabLearn curriculum, they prototyped the first FAB! workshop.

The workshop curriculum consists of two phases spanning four consecutive weekends. The first 40 hours are spent learning the ins and outs of digital fabrication: how to use a 3D printer, a laser cutter, a microcontroller, basic programming, and electric circuits. Once they are equipped with the necessary tools and skillsets, the students move into phase two, where they brainstorm real problems that affect them. Then, they break up into teams according to their interests, generate ideas, and prototype them.

In addition to forming friendships among their peers through team building, the kids gain role models in the form of the program mentors. College and graduate students majoring in engineering, industrial design, or education are trained to guide the young learners through how to use the tools and build their prototypes. In keeping with the design thinking methodology, the mentors know to question the students rather than provide them with the answer. “This way,” Calderón explains, “the students learn that you should never say ‘I can’t do it;’ it shows young people how to find an answer for themselves.”

The students learn that you should never say ‘I can’t do it;’ it shows young people how to find an answer for themselves. Tweet This Quote

To date, FAB! has worked with 300 high school students who have generated over 30 working prototypes for solving real issues in Mexico.

Though slightly less measurable, perhaps the biggest symbol of FAB!’s impact is the change in the children’s perception of themselves. “The kids arrive feeling a little shy, and not wanting to study some kind of career because they don’t believe in themselves,” says Calderón. “They end the course feeling more secure and more excited to continue their studies.”

Students creating a Rube Goldberg Machine: an elaborate device created to perform a mundane task. Photo courtesy of FAB!

Calderón’s favorite example of this is a story about a boy named Damián. With his teammates, he made a water filtration device that collected rainwater from the roof and passed it through a series of materials to purify it. A microcontroller at the end of the filtration process reported the purity of the water. Damián ended up developing this project further to win a national science competition. He then was invited to an international competition in Argentina, where he won the top prize again.

From these triumphs, Damián’s perspective changed completely, “because of what he could do and learn for himself,” Calderón explains. “Damián told us that some of his teachers would tell him and his fellow students that they could not aspire to be more than workers. He told us that this achievement felt unimaginable to him before.”

This transformation is what Calderón and Otero want for every child that participates in FAB! “We love to see how young people are dealing with their frustrations by generating solutions,” says Calderón. “At the end of the workshop, they feel capable of studying or doing whatever they want.”

Students at a workshop hosted at the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education (TEC.) Photo courtesy of FAB!

FAB!’s vision is to continue changing the mentalities of young people in Mexico, which will in turn change the future of Mexico. Their plan is to first establish developed programs in two major cities and solidify a team that sustainably generates workshops both within and outside of school programs.

FAB!’s vision is to continue changing the mentalities of young people in Mexico, which will in turn change the future of Mexico. Tweet This Quote

Ultimately, their vision is rooted in the belief that everyone should have the opportunity to realize their full potential, as that positively ripples throughout a community. Calderón sees this not only as an opportunity but also a responsibility.

“Our belief is that we are all agents of change, and everyone is an expert of their own environment,” explains Calderón. “Thus, who better to fix a problem than those who know it best?”