Global Issue

Illiteracy

Series

If You Can Read This

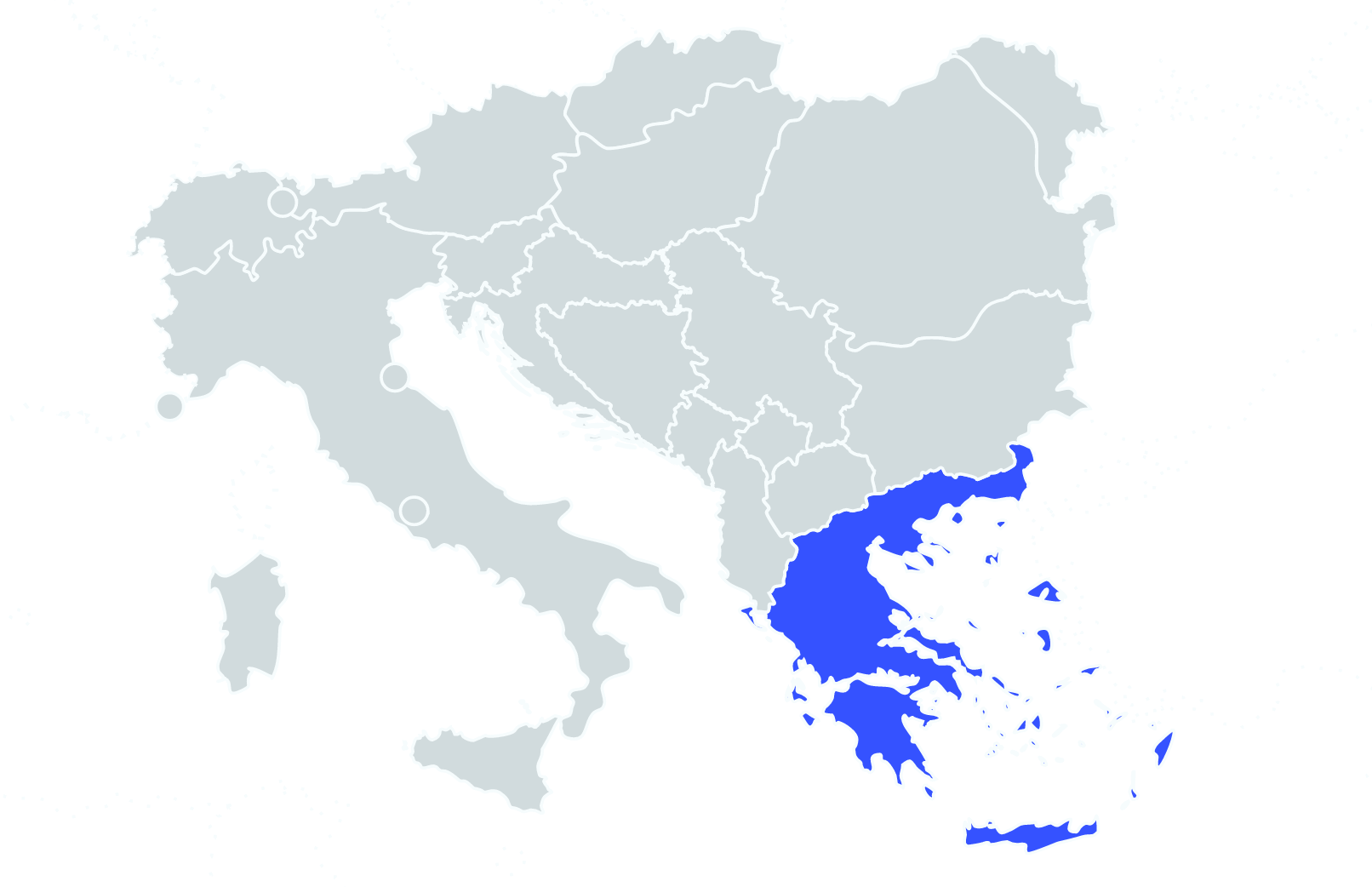

On a hot June afternoon in Greece, Miriam takes a train from Oinofyta to Athens with two other friends to apply to attend Greek school later in the summer. After their appointment, they separate when the friends decide to go visit family members living in another refugee camp outside of Athens. But Miriam left her six-year-old boy taking care of his younger brother at their camp in Oinofyta, so she needs to make it back “home” before dark. She knows her way to the train station. But when she arrives amid the bustle of people coming and going in transit, she freezes in front of the long row of platforms.

She has to go back, but she has no idea which train to take.

Miriam is 22 years old and even though she has acquired an uncommon array of skills over the course of a childhood spent in a country at war, they are of no use to her now. Shepherding, narrowly escaping the Taliban, navigating the migrant trail to Western Europe — none of these experiences will help her find out which train to take, or how to ask anybody for directions.

Miriam has never opened a book or held a pen. But now that the Greek government has opened a small quota for refugees to attend school, she’s taking on the biggest challenge of her life: wanting to learn how to write, read, and speak a new language in a strange land. But today she only applied to become a student. She still doesn’t know how to write, read, or speak Greek or English.

Puzzling over the line of platforms, Miriam begins to cry. Every so often, someone offers her food or money, but their gestures only confuse her more.

Shepherding, narrowly escaping the Taliban, navigating the migrant trail to Western Europe — none of these experiences will help her find out which train to take.

Literacy can be both the key to and the barrier against personal wellbeing and success. Imagine trying to learn a second language when you can’t even read or write in your first. This is the reality for over 3.5 million registered refugees worldwide. And even though governments understand that literacy is absolutely vital to refugees’ integration, work, and independence (as well as their ability to plan a future in their host countries), the current “one size fits all” approach is not helping.

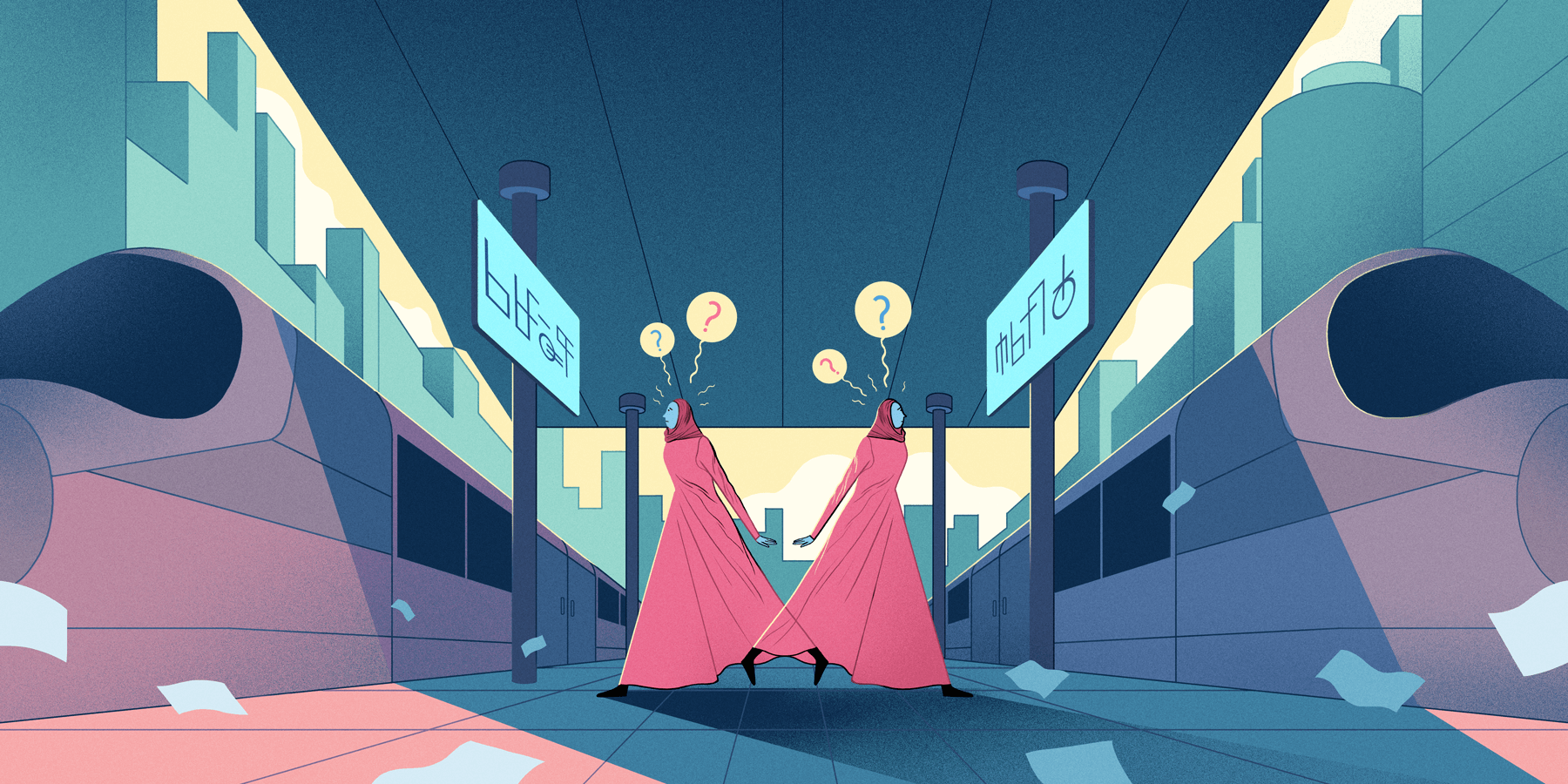

If someone who has never in her life held a pen finds herself sitting in a classroom next to someone with a university degree who can already speak English, what chance does she stand of keeping up?

Governments and NGOs label refugees with the same word and create the same “solution” for all of them, without considering that they have unimaginably diverse backgrounds, particular challenges, and needs. There are refugees who were educated back home and who would say it’s easy to learn the language of their host country, because they know how to read books, navigate the internet, watch videos, and listen to music.

But there are millions of others who are attending classes yet still use an interpreter or a friend just to help them get through their days. Some of them want to learn how to write and read in another language so they can go to college and create a better future for themselves. Others just want to become literate so they can go to the doctor on their own. Some simply want to have enough privacy to read their own letters.

Illustration: Rune Fisker

This is why Miriam wants to enroll in school in Athens, but she doesn’t yet know that she is facing an uphill battle, and that she will be sitting next to other students who are already literate and who know how to speak Greek and English.

Refugees are not mainstream students and cannot be treated as such. Their diverse educational experiences and learning styles should not be disregarded. The issue demands a different type of innovation to fill in the gap.

Efforts to open refugee quota in existing schools or having grassroots organizations open temporary classrooms in refugee camps does not come close to sufficing. None of these stopgap measures make use of technology or the internet to meet the needs of this market niche. Using mobile phones, laptops, and tablets allows people to learn and to access information and material at anytime, anywhere.

As entrepreneurs, as innovators, as anyone capable of reading a sentence, we need to wake up to this huge market opportunity.

The ability to pack thousands of different educational resources into a single device would support diverse learning styles and avoid perpetuating assumptions about the educational history of students who are refugees. Language learning, teacher training, support networks, and the wealth of information on the internet, such as news channels, films, lectures, educational games and online libraries, can all make literacy accessible for refugees. Such solutions would also lower costs for governments and NGOs that are currently investing resources in very unstable camps and communities.

Imagine if, as Miriam stands on the platform, frightened and confused, she could use her own phone to communicate with people around her or to find out which train to get on to go back to her boys? Instead, to escape from the situation she created at the station, she’ll jump on the next train that opens the doors in front of her and travel in the wrong direction, towards the airport. Luckily, she’ll run into two English women who know enough Dari to direct her home. But her experience is one lived out by refugees hundreds of thousands of times daily, to many less fortunate ends.

As entrepreneurs, as innovators, as anyone capable of reading a sentence, we need to wake up to this huge market opportunity and make strides towards improving resources and methods of education provided for refugees. There are sixty million people hungry to use a product that we have yet to create. Whoever among us overturns this market failure will empower refugees to rebuild their lives, and ultimately, to regain their dignity in this world.