When you think about chocolate, what comes to mind? Maybe brownies, truffles, or thick chunks of dark chocolate. Do you know where chocolate comes from?

For most consumers, the answer to this question might stop at “the supermarket.” Maybe you’ve heard of cocoa beans, or are a fan of raw cacao, or cacao nibs. But did you know that the chocolate we know and love comes from a fruit tree?

Chocolate is a massive global industry, with an estimated value at over $100B in 2015.

Chocolate originates from the plant Theobroma cacao, a tropical fruit tree that grows football-shaped pods that shoot out directly from its trunk and branches. Inside the pods are glistening purple seeds, entirely housed in pockets of fleshy white fruit. While the tree’s genetic origins are rooted in the Amazon basin around Ecuador, Peru, and Brazil, over 70 percent of the crop is now produced in West Africa.

Chocolate is a massive global industry, with an estimated value at over $100B in 2015. The U.S. and Europe constitute the largest markets by far, with the average consumer eating more than 11 pounds of chocolate per year.

For a long time, the only chocolate available to consumers consisted of industrial confectionary products, ranging from low-cocoa-content candy bars (Hershey’s, Snickers, Reese’s, et cetera), to mass-produced chocolate chips for home baking, to cocoa powder.

What do these mass-produced products have in common? The mega-brands behind them make little to no effort to educate about, promote, or even disclose the source of the cacao beans used in their products. This has left the vast majority of the chocolate-consuming populace unaware of the journey that cacao travels from tropical origin to supermarket shelves.

The result? Massive over-commoditization of the cocoa industry. Widespread poverty of cacao farmers, most of whom are earning less than $2 per day from cacao farming. More than two million kids working in cacao, 96 percent of whom are in the worst forms of child labor. Large-scale destruction of tropical rainforests, pushing chimps and other animals to the brink of extinction. Rapidly consolidating large cocoa traders and chocolate manufacturers seeking to lower costs and increase profits at the expense of poor communities and the environment.

Forests and farmers to blame?

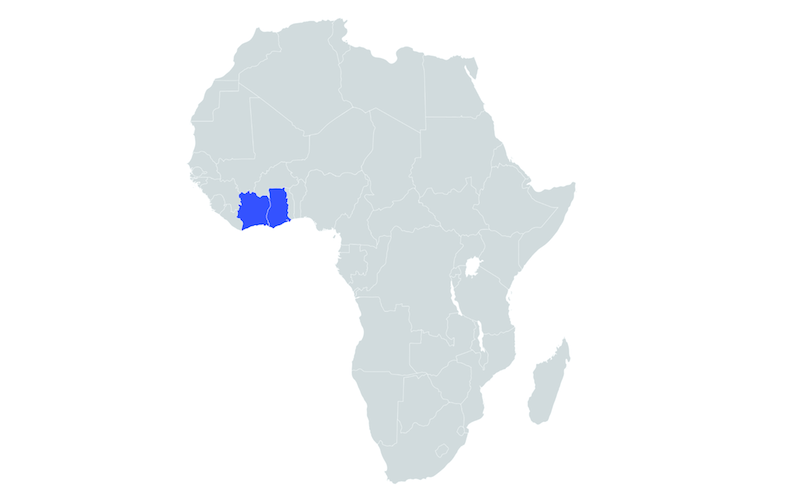

A 2017 investigative report published by the NGO Mighty Earth informed the industry at-large about the enormous problem of deforestation. The report focused on Ghana and Ivory Coast, the world’s two largest cocoa producing countries, who grew and exported 2.3 million metric tons — or 52 percent — of the world’s cocoa in 2016.

Ghana and Ivory Coast have lost around 90 percent of their forests, one third of that for cocoa.

Ghana and Ivory Coast have lost around 90 percent of their forests, one third of that for cocoa. Less than 11 percent of Ivory Coast remains forested. Satellite maps from 1990-2015 show the dramatic impact of deforestation on this country, where now only 200-400 elephants remain from an original population of hundreds of thousands.

National parks are being invaded for the sake of growing cocoa, with Ghana losing nearly 300,000 acres of protected area between 2001 and 2014 to cocoa production. In Ivory Coast, it’s estimated that 90 percent of the land mass of at least seven of 23 separate protected areas was converted to cocoa farms.

The resulting carbon footstep is astounding: According to Mighty Earth, a single dark chocolate bar made with cocoa derived from deforested areas produces the same amount of carbon pollution as driving 4.9 miles in a car. Then try multiplying the impact by the billions of chocolate bars consumed by Americans alone each year.

Government corruption in these countries, or even farmers themselves, are most frequently blamed as the source of the issue. The reality is that farmers in Ghana typically earn as little as $0.82 per day producing cocoa, and in Ivory Coast, only a meager $0.54.

The persistent and unfounded low prices and undervaluing of their crop, driven by the industrial chocolate market and consumers who don’t know any better, has locked farmers into a vicious cycle of poverty. This poverty is the single most important causal factor of the slave labor, child labor, and deforestation that persist in the chocolate supply chain.

So, it’s little surprise that farmers are invading protected areas to plant cocoa, or insisting that their kids stay home from school to help harvest cocoa. Simply put, they have no other options. The combination of land insecurity and growing populations makes choosing to improve or replant existing farms too expensive, and so clearing virgin forest becomes their cheapest option.

The only true solution to these problems is working to end cacao farmer poverty. We, as chocolate lovers and active consumers in the chocolate industry, must recognize there is a problem with the market structure itself, and that we must fix it.

Fresh cacao fruit from fields near the Caoba natural reserve in Colombia. Photo: Tijs Zwinkels

Crafting a new market

The cocoa commodity market is structured like all commodity markets, in which the product being traded is “fungible.” Cocoa from one country is exactly the same as cocoa from another country, so contracts for purchase of cocoa can be traded as financial instruments. Hedge fund managers play the market, betting on the rise and fall of cacao prices. In turn, the real prices farmers earn in countries as far-flung as Indonesia and Peru are affected daily by the speculation of these fund managers and others who, alongside rumors of harvest productivity or weather events, can send cocoa prices flying or sinking over the course of hours.

The only true solution to these problems is working to end cacao farmer poverty.

To make matters worse, sensationalist headlines about cocoa deficits, along with the misguided notion that improving cocoa farming productivity is the key sustainability solution for farmers, have led to significant increases in year-over-year in cocoa production globally. However, global cocoa demand is staying relatively flat. Currently, there is an oversupply of 15 percent expected to persist for years.

The chocolate world, however, is now changing. A new market, known as “craft” chocolate or “bean-to-bar” chocolate has emerged. What began humbly as a handful of makers in the early 2000s has blossomed into a movement of hundreds of companies — makers who require high-quality beans with flavor and integrity, who widely disclose the origin of the bean.

Most importantly, they — and their customers — are willing to pay more to ensure farmers have better livelihoods, human rights are protected, and forests are cherished.

An entirely new, de-commoditized supply chain is needed to meet the demand of these craft chocolate makers. Quality must be carefully controlled across the supply chain: from farm, through fermentation and drying, to export. This new supply chain is creating the necessary fundamental steps to improve the lives of farmers at origin, all while reducing the negative environmental impact and deforestation resulting from cacao growth.

An Uncommon Solution

If we have any hope of realizing a new cocoa supply chain, then prices must be transparent. Transparency is a key part of making the chocolate industry truly sustainable. That is exactly what my company, Uncommon Cacao, has been building since 2010 in cacao-producing countries across Latin America.

We work directly with farmers in Guatemala and Belize, visiting farms to map out the farms’ boundaries, assessing and promoting agroforestry, and understanding labor practices and farmers’ realities. We partner with exporters in other countries that pass our rigorous Supplier Scorecard; and once they do, we pay them significantly more.

Exporters in our network earned on average 163 percent higher than the commodity cocoa price.

In 2017, farmers in our network earned, on average, two times what most farmers earn in Ghana or in Ivory Coast. Exporters in our network earned on average 163 percent higher than the commodity cocoa price. In 2018, Uncommon Cacao will begin working with a farmer association in Ghana that has emerged as a leader in traceability, transparency, elimination of child labor, and quality.

On the ground, the impact of our model is visible. Farmers invest in planting new hardwood and fruit trees intercropped among their cocoa. They choose to preserve areas of their farm as biodiversity habitats, never to be touched for commercial cocoa production. This kind of cocoa, often called “agroforestry” or “shade-grown” cocoa, is the key to making chocolate truly forest-friendly – unlike the vast “full-sun” monocultures of industrial cocoa.

Our farmers’ kids are going to school, and are coming back to train cocoa farming communities in better production practices. Farmers are choosing to produce organically, understanding the long-term impact of intensive chemical use on their soils and the surrounding ecosystems. This preserves water quality in rivers, which is vital for many remote rural communities who depend on natural waterways, without the luxury of water piped in.

Social change takes social investment. We cannot expect farmers or governments to stop engaging in practices that enable them to cover their basic costs and seek better futures for their families. Instead, the onus is on us — as cocoa buyers of all kinds — to insist on transparency in the supply chain, pay more for chocolate, and care about where our cacao comes from. We can all be part of the problem, or part of the solution.