Global Issue

Illiteracy

Series

If You Can Read This

Of the three billion people who live in rural areas in developing countries, two-thirds earn their livelihoods by farming small, one- to two-acre plots. Most of them live in poverty.

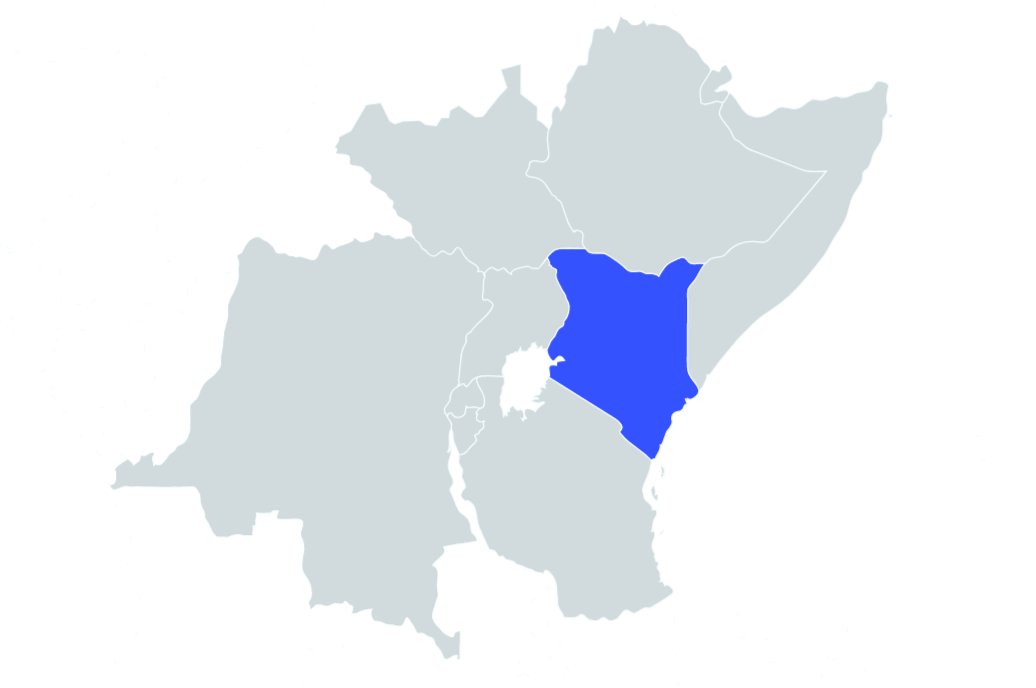

In Kenya, even though smallholder farmers produce 63 percent of the country’s food, they earn less than $3,000 USD a year on average. The irony is that these farmers often can’t adequately feed their own families. Unable to cover the costs of basic human needs, they can’t justify paying the fees necessary to send their children to school. When it comes to global literacy rankings by country, Kenya falls on the cusp of the bottom third.

For Samir Ibrahim, co-founder and CEO of SunCulture, a solar-powered drip irrigation company based in Nairobi, this doesn’t sit well.

“Farmers grow our food,” says Ibrahim. “There’s no reason they should be hungry and some of the most marginalized people in the world.”

Farmers grow our food. There’s no reason they should be hungry.

Because Ibrahim’s family immigrated to the United States from East Africa in the 1970s, he was drawn to solving problems in the region. In business school at New York University, he met Charlie Nichols, who conceptualized and developed the technology behind solar-powered drip irrigation. Together, they knew they could build a solution that would make economic sense for farmers. So, they entered a business competition.

The duo placed second. Undeterred, five weeks later Ibrahim had raised a small friends and family round of funding and was on a plane to Nairobi.

SunCulture, co-founded in 2013 by Ibrahim and Nichols, works at the intersection of technology and agriculture to improve crop yields, conserve water, and above all, help East African farmers increase their annual income. In this case, the latter correlates significantly with education.

“When we surveyed our farmers, 61 percent of them say the first thing they spend their money on is school fees,” says Ibrahim. “If a farmer can’t afford to hire workers, their kids will work. If they can hire workers, then their kids go to school.”

Robert Bunyi started farming with SunCulture in March 2016 with two acres of land in Kenya. As they do with all of their customers, Ibrahim and his team worked closely with Bunyi for months to better understand his needs.

SunCulture works at the intersection of technology and agriculture to improve crop yields, conserve water, and above all, help East African farmers increase their annual income.

At the time, he knew hardly anything about agronomy. He was not irrigating his land, even though erratic weather and frequent droughts in the region make consistent crop yields difficult. Irrigation brings more consistency, but traditional methods cause the global agricultural sector to consume about 70 percent of the world’s freshwater, much of which goes to waste.

Bunyi explained to Ibrahim that he needed something more reliable than rainfall that didn’t require access to the electrical grid or fuel – and something at a price point he could afford.

Conversations like these with Bunyi help to continually fine-tune the components of SunCulture’s AgroSolar Irrigation Kit. Solar panels generate electricity that pumps water up from a nearby source, like a river or a well, and then stores it in a raised tank. By opening a valve and utilizing gravity, farmers control the movement of a dependable water supply down through the irrigation system to their crops – no matter the time of day or year.

SunCulture customizes the components of its kits from data gathered by in-field technicians. No two farm plots look identical, so the company has to survey the land of each prospective customer to ensure the irrigation kit will contain the right ratio of parts in order to fit their needs.

For many SunCulture farmers, their yields can increase by up to 300 percent. This farmer showcases some of his potato harvest. Photo: SunCulture.

Additionally, farmers like Bunyi have taught the SunCulture team that they need to train the farmers. Many farmers have never studied agriculture or irrigated land before, much less seen solar panels. Through creative social media, radio, and television campaigns as well as persistent in-person visits, the team has succeeded in capturing and retaining customers. To Ibrahim, it’s the “farmer-led invention and reinvention” that has helped the team earn the trust of those they serve.

To date, SunCulture has reached and helped raise the incomes of around 700 smallholder farmers directly, who each hire five people on average. SunCulture farmers make $14,000 USD per acre, per year, on average, and some have increased their yields by 300 percent.

Despite massive economic improvement for many farmers to date, Ibrahim says the biggest barrier to more widespread adoption is the high upfront cost of the irrigation system. Kits that irrigate one-acre plots cost approximately $385 USD.

We’re now piloting and rolling out the world’s first pay-as-you-go enabled solar irrigation solution.

“What keeps me up at night is knowing there are still many farmers who can’t afford this,” says Ibrahim. “What we’re doing now is piloting and rolling out the world’s first pay-as-you-go enabled solar irrigation solution.”

This financing option, according to Ibrahim, will unlock an entire suite of services and products to get farmers the capital they need to start farming more effectively, increase their yields, and earn more money.

“My yield is now four times what it was before,” says Bunyi. “I have too much to sell, which is a good problem to have. I never had that before. Soon, I’ll be providing the best quality lettuce in the country.”