They’re the face of the only country in which they can survive in the wild. They cling to the native eucalyptus trees and spend their days eating the leaves and sleeping. They are an iconic animal of the Australian East Coast, and they’re in trouble.

Eucalyptus forests span the entire East Coast of Australia and create the only habitat and source of food for koalas. Equipped with digestive systems developed to consume only eucalyptus leaves and hindered by slow motor skills on the ground, koalas depend on these endemic trees for the very basis of their survival.

Previously, the abundance of eucalyptus trees in Australia provided ideal conditions for thriving koala populations, however, with shifts in regional economic focus, this has not recently been the case.

“We’re going to lose the koala and with the koala we’re losing so many other animals.”

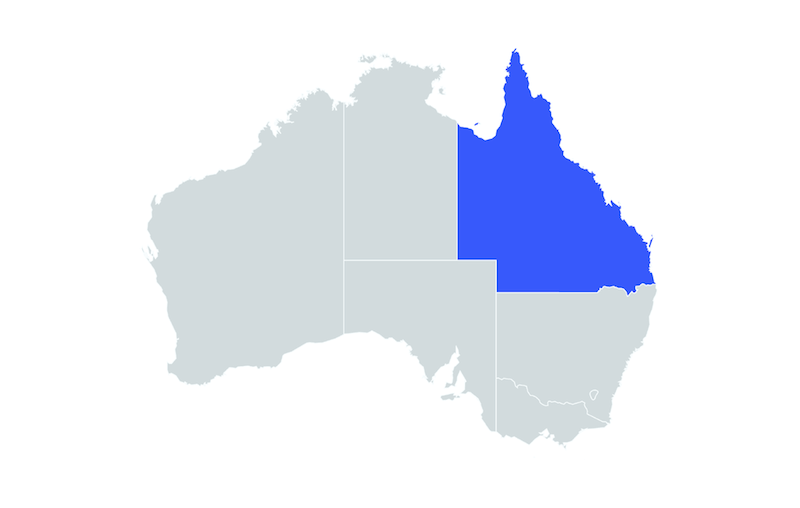

Increasing emphasis on development and expansion in the northernmost state of Queensland has failed to account for the massive amount of acreage of koala habitat sacrificed to sanctioned clearing and construction projects. Not only is this habitat critical to the survival of several species of indigenous wildlife including the koala, but it also takes years to replace.

“There’s no holding back at this point,” says Anika Lehman, President of the Moreton Bay Koala Rescue, over the phone from her home in Queensland, Australia. She runs the volunteer-based team with the sole purpose of rescuing endangered koalas and releasing them throughout the state.

“We’re going to lose the koala and with the koala we’re losing so many other animals.” She pauses, then gravely relates that every three seconds a football field’s worth of critical habitat trees are lost due to development clearing in Queensland.

“It’s devastating, and it’s not nice to actually say it, but that’s the truth.” she says.

As it stands today, koalas are listed as “regionally vulnerable” in the Australian states of Queensland and New South Wales, meaning the population has seen a 30-50 percent decline and has a 10 percent probability of extinction in the next 100 years. Although achieving this listing status may resemble a promising step for advocacy, not much has been done since to help the situation.

The koala was finally listed as vulnerable as a part of the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC) in both states in 2012, 12 years after it was first suggested.

According to the Australian Koala Foundation (AKF), the koala was finally listed as vulnerable as a part of the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC) in both states in 2012, 12 years after it was first suggested. The hope was that the listing might initiate new policies that would protect koalas from habitat loss and land degradation. This has not been the case.

Lehman blames the apparent lack of will from the government.

“None of the government levels is strong enough to stand up and say, ‘This is it. We need to do something different.’ Everyone is passing the buck,” she says. “The state government says it’s the federal government that should make the laws, the federal government says it’s the council, the council says it’s the state. Ultimately, no one is doing anything.”

Lehman has witnessed first-hand the apparent lack of urgency and care from government officials surrounding this issue. In a meeting with a former Minister of Environment, she was given the explicit impression that frankly, government officials’ lives would be easier if the koala “would just go extinct.”

“And that’s our problem. They really, really don’t care,” Lehman says.

Eucalyptus forests serve as the only habitat koalas can survive in. Koalas possess poor motor skills that severely handicap them on the ground, so trees and their leaves provide a vital source of both shelter and food.

Current Legislation Isn't Working

T he EPBC Act is the only standing legislation intended to protect endangered animals throughout Australia, and it isn’t working. As each state has its own legislation regarding wildlife, they all propose their own wildlife management drafts. State policies have integrated the drafts in the past in an effort to show the public that the government is trying to come up with new solutions, but to little actual avail in the case of the koala.

In 2008, the Queensland Government created the Koala Task Force assigned with the responsibilities of data collection and habitat mapping for the dwindling koala population. The task force compiled and reported a list of recommended actions the government should take in order to protect and possibly reverse the damage that was already done to koala habitats.

These recommendations included implementing policy that results in “no net loss of the koala habitat in Southeast Queensland.”

An interim report was published in 2017 in which the Queensland Koala Expert Panel, established in 2016, compared the key actions listed by the Koala Task Force to the implementations the government put in place to satisfy the Task Force’s suggestions. The report reveals that despite the ideal objective of no net loss of koala habitat, “the vast majority of the actions implemented were only ever likely to result in a slowing of the loss of habitat, rather than halting loss.”

These recommendations included implementing policy that results in “no net loss of the koala habitat in Southeast Queensland.”

Lehman and other activists have seen little to no movement towards legitimate, maintainable legislation that protects the wildlife of Queensland, however, Leeanne Enoch, the current Minister of Environment, seems more optimistic about the future efforts of her administration.

Following their establishment and critique of the Koala Task Force, the Queensland Koala Expert Panel created six recommendations that they believe will better protect the koala habitat.

“The government has accepted the Koala Expert Panel’s six recommendations,” Enoch says. “We are now developing a new South East Queensland Koala Conservation Strategy to identify the actions we will take, and the work we need to do with our partners, to meet the Panel’s recommendations.”

While this promise may sound all too familiar to Queensland’s activists, the government’s persistence in dedicating resources to develop a solution does hint at a silver lining for the dwindling koala population in the northeastern state. On the whole, however, Australia still faces a substantial wildlife crisis in several other states.

Under the EPBC Act, the national efforts to provide protection for koala habitat seem questionable. The Act itself lays out a framework for companies to consider when planning their development projects, and states that any action that could potentially have a significant impact on a vulnerable species must be approved by the state’s council.

According to the Act, a “significant impact” includes actions that will “lead to a long-term decrease in the size of an important population of a species” or “modify, destroy, remove or isolate or decrease the availability or quality of habitat to the extent that the species is likely to decline”.

So why, with this national policy in place, is the koala’s habitat still in decline? Many activists, including Lehman, say the loopholes found within the legislation allow developers to get away with nearly every project that requires forest clearing.

Such loopholes include vague language describing what constitutes koala habitat. The EPBC Act promises to protect land that is “habitat critical to the survival of the koala.” Without a clear definition of what exactly qualifies land as “critical habitat,” development companies can easily capitalize on ambiguity to manipulate council decisions.

“It’s so frustrating. You might have a win because you slow a development for six or nine months, but eventually it all goes ahead because the developers will find the loopholes to do whatever they need,” Lehman says.

Every three seconds a football field’s worth of critical habitat tress are lost due to development clearing in Queensland.

Same Problem, Different Crisis

The same lack of political heedfulness has had an effect in the state of South Australia, to a different effect.

W hile most of the calls for policy change involving koala habitat degradation arise from Queensland and New South Wales, the same lack of political heedfulness has had an effect in the state of South Australia, to a different effect.

Kangaroo Island, South Australia, is considered the Galapagos of Australia. With a mild climate and protection from harsh Pacific winds and tides, much of Australia’s unique, native wildlife flourishes with little disturbance. The island is also legally conserved through the joint efforts of National Parks, Conservation Parks and Wilderness Protection Areas, Heritage Areas, and privately owned land.

Conservation of this habitat is of obvious importance, yet optimal survival conditions have lead to the overpopulation of many species, including koalas. In the 1920s, eighteen koalas were introduced to the island in an effort to protect the animal from the growing fur trade, and by 1997, that seed population had multiplied into the tens of thousands. According to the South Australian government, as of 2017, the state’s koala numbers had tripled over the course of only five years.

When privately owned companies took advantage of the island’s isolation to turn more than 14,483 hectares of land into blue gum tree plantations, the abundance of food and territory resulted in the overpopulation of koalas.

The problem the island now faces is two-fold. The overpopulation of koalas in the south causes loss of food and habitat for other animals on the island, and until a recent sterilization program was passed, South Australia had no ethical way of controlling the expanding population.

On the other hand, the investment deals that were made to plant the blue gum trees in the early 2000s have since fallen through, leaving the plantations available to be cut down, but under no legal ownership. Kangaroo Island Plantation Timbers have since taken over the plantations and plan to create what is expected to be a lucrative timber trade, yet without framework, final approval, or a wharf for exportation, the problem remains far from solved.

“We’re seeing two extreme opposites in the same country and now we need to decide how we’re going to balance the two issues at once.”

Gordon Rich is a chemical engineer for Wombaroo, a company based in Adelaide, South Australia, that supplies species-specific milk to zoos and rehabilitation centers across the country. The intention of the company is to provide a milk product that is as close as possible to the milk that varying species of animals, including marsupials, receive in the wild.

“We’re seeing two extreme opposites in the same country and now we need to decide how we’re going to balance the two issues at once,” he says, regarding the overpopulation of koalas in his home state and their potential extinction in others.

Increased development in areas containing vital native koala habitat is currently responsible for 72 percent of koala deaths.

A Solution That Starts With Acceptance

A s rehabilitation centers see an increasing number of orphaned joeys that need to be integrated into the wild, demand for milk supplement continues to grow throughout Australia. Some of these joeys lose their mothers due to disease, but most lose their mothers to accidents arising from increased human interaction caused by habitat loss.

“We are seeing animals with injuries that we would never have seen 20 years ago,” Rich says.

For example, koalas are commonly struck and killed by trains that now run through their habitats. They are also found dead or with serious injuries from car accidents, domestic animal fights, and construction machinery and materials — all evidence of excess interaction with adjacent human populations and development.

One particularly bizarre solution suggested by officials encouraged the readoption of daylight saving time, which researchers claimed would decrease the number of traffic accidents involving the koala because drivers would have an extra hour of daylight to see them crossing the road.

Perhaps the greatest barrier to developing truly viable solutions is the discrepancy in data used by the Australian government and the AKF when determining the number of koalas left in the wild.

According to 2013 AKF research, the Australian government’s estimates of remnant wild koala populations are five to 10 times greater than their own estimates, warping the data and effectively diluting the urgency of the issue. While government research expenditure capped at $50,000, the AKF implemented $8M in its efforts to gather data, map habitat, and track koalas.

The AKF estimates, for instance, that only 17 percent of Australia’s original koala population remains, whereas the government places the number at 72 percent.

“I think there’s only one solution to save our wildlife, and that is to stop clearing. It’s that simple.”

This alarming discrepancy in population estimations only further legitimizes Australia’s predicament. It also begs the question: if the government doesn’t accept the extent of the problem, how will it develop legislation that will fix it?

While experts continue attempting to design the next koala-saving resolution, Lehman and many others are satisfied with the most obvious answer.

“I think there’s only one solution to save our wildlife, and that is to stop clearing,” she says. “It’s that simple.”