Why does one startup get picked over another for funding?

From the entrepreneurs point of view, the answer to that question is often asked in frustration, as they are turned down by yet-another investor, or passed over by yet-another accelerator program.

Why does one startup get picked over another for funding? Tweet This Quote

I feel for those entrepreneurs, as I spend most of my life on their side of the table. However, periodically I step over to the other side, sometimes as an Angel investor, then twice annually when it’s time to pick the handful of “fledgling” invitees into Fledge, my conscious company accelerator. I much prefer being my role as entrepreneur and advisor, but nothing beats these periods across the table to understand the thought processes of investors.

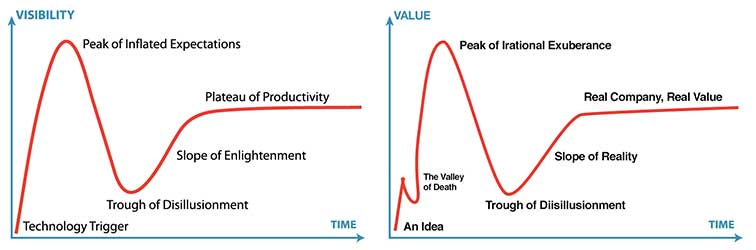

One surprising, non-intuitive thought process is in valuing early-stage startup. Values for startups mirror Gartner’s “Hype Cycle,” which helps explain the excitement around new technologies. This comparison is true for all companies, not just technology companies.

On the left, the “Gartner Hype Cycle” by Jeremykemp at en.wikipedia.

On the right, the “Startup Value Hype Cycle” by the author.

For startups, the very start of the curve matches the era of PowerPoint and promises, before any meaningful sales, before the plan has enough proof to prove it might work. At this stage, the entrepreneurs are often dreaming of their business at scale, but the investors are demanding some proof that the dream might come true. At this stage, the value is at its lowest. At this stage, the entrepreneurs are the most frustrated, wondering why the investors are passing by (see If you think it… they will fund).

On the way toward reality, entrepreneurs then reach a spot that is missing from the Hype Cycle. It is the Valley of Death or less morbidly, the Pioneer Gap. This is the next frustrating moment, when a company needs something (most often money) to reach the next milestone, to close the first customer, to prove out the business. Many startups die for lack of bridge across this valley, as few investors like to pay for the added risks at that stage.

The most interesting part comes next, the irrational exuberance, the equivalent of the Peak of Inflated Expectations. For a startup, this is the moment when it seems the business model might work, when that initial traction is sufficient for investment, but before either the entrepreneurs or investors know what will likely go wrong. It is at this stage that the opportunity seems largest, and thus the value of the company is often (in future hindsight) inflated beyond reason.

This is the moment where investors don’t just believe the story, but dream of potential futures. Disruption. Big exits. IPOs. “Changing the world.” If you are an entrepreneur, this is your moment to seize the day, start to fundraise, and if you are lucky, grab enough momentum of illusions to close a first round of funding. The timing needs to be perfect, however, as this peak can disappear with any bad news.

If you are lucky enough to find funding, or if you manage to push through somehow without funding, then the next stage once again turns unintuitive, the Trough of Disillusionment. This is after a company has customers. Often after any initial funding has been spent. Too often, after the planned (and promised) milestones have not been met, due to those unforeseen hurdles hiding from the view on the Peak.

At the end of the curve is the real world of business, where the craziness of startup funding is a memory, where the real world of finance, banks, lines of credit, and loans awaits the successful startups.

For some startups, the Peak lasts beyond the first round of funding. For Groupon, it lasted past their IPO. But for most, the peak passes quickly, and the company suddenly finds that investors now value the company based on revenues, or yet-reached profits, or other hard measures that don’t reach the heights from that previous Peak. It is in this stage that the dreams of scale disappear, as the realities of the chosen market become clear, the limitations of scale understood, and the complexities of operations exceed all original plans. It is here that in hindsight the original financial plan looks irrationally high in revenues, and absurdly low on expenses.

If a startup survives its Trough of Disillusionment, growing sales, operating the business, doing what it needs to do, then it eventually finds itself on the other side, a real business with real value, with profits and a value based on similar real businesses. At the end of the curve is the real world of business, where the craziness of startup funding is a memory, where the real world of finance, banks, lines of credit, and loans awaits the successful startups.

This originally appeared on Luni’s blog.