The current usage of the word unicorn makes me tired. I could rant about it for a while, but that would make me tired of myself ranting about it.

Instead, I’d like to focus on a word that appeared a month ago by Aileen Lee in Welcome To The Unicorn Club, 2015: Learning From Billion-Dollar Companies. That word is unicorpse.

From section #6 in Aileen’s post:

The word showed up again in Nick Bilton’s Vanity Fair article Is Silicon Valley in Another Bubble…and What Could Burst It?

We basically doubled the number of unicorns in the past year and a half. Tweet This Quote

Erin Griffith had a perfect chance to use unicorpse in her article VCs have ‘Dying Unicorn’ lists, but they aren’t sharing them, but she missed the layup and went with dying unicorn instead.

Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff predicts dead unicorns, as startups seem to focus more on their valuations than their customers. Tweet This Quote

Now, I don’t blame Aileen for the word unicorn. And I credit her for unicorpse, which I expect will be a lot more prevalent in the future. It’s not, in Bilton’s language, schadenfreude on my part. Instead, I believe that by focusing on the concept of a unicorn, we are paying attention to exactly the wrong thing.

I once simultaneously sat on the boards of three public companies that were all worth more than $1 billion. One went bankrupt, one was acquired for $0.14/share ($40m), and one was acquired for $0.025/share ($25m). I think you can call two of them as unicorpses and one of them a unicorpse with nothing left but dust where the bones should have been.

By focusing on the concept of a unicorn, we are paying attention to exactly the wrong thing. Tweet This Quote

Don’t feel bad for me. I once was on the board of a company that had generated lifetime revenue of $1.5m and was acquired by a public company for $280m of stock which, by the time the deal closed, was worth around $1.1 billion. Two years later, the public company (which at one point was worth over $30b) was bankrupt.

None of these companies were ultimately worth $1 billion or more. Each of them stumbled for different reasons, but a lack of obsessive focus on product and customer was a big part of why they vaporized. They assumed, regardless of how much capital they had, that they could raise more. They didn’t focus on building a long term, sustainable business that had a huge protective moat around it. I don’t care how disruptive you are—if you don’t build a moat, someone is going to come disrupt you.

It doesn’t matter how disruptive you are—if you don’t build a moat, someone is going to disrupt you. Tweet This Quote

I’m encountering an increasing number of companies with burn rates in the stratosphere. I get uncomfortable when the net burn rate for a company goes above $500k/month. In fast growing companies with a balance sheet > $25m I can stomach a $1m/month net burn. But when I see $2m/month net burn rates, I vomit. And a $4m/month net burn rate, even if you have $100m on your balance sheet, makes me physically ill.

As an investor, would I rather own 30% of a company that is acquired for $300m in cash that had only raised $10m or 2% of a company with a paper value of $1b and $200m of liquidation preferences? As a founder, would you rather own 10% of the company that sold for $300m in cash or 2% of a company with a paper value of $1b and $200m of liquidation preferences? There is a lot more in the calculation of value, especially who gets what, than that $1 billion unicorn thingy.

Let me say it in a different way:

There is nothing special or valuable about a $1 billion valuation. It’s just a number. Tweet This Quote

I’m not predicting a bubble or anything else. I’m not negative about where we are at in the cycle. I hope to live another 50 years, as I think this is going to be the most interesting point in the history of our species up to this point.

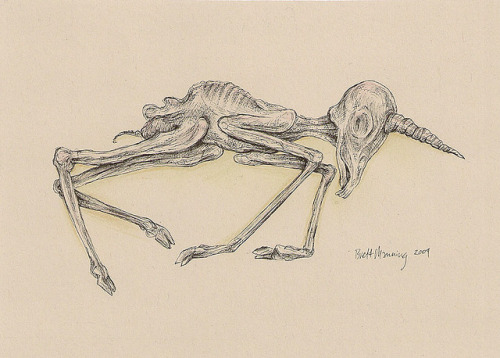

But I do think it would be useful for more founders and investors to ponder unicorpses and spend less of their energy talking about, and trying to become, unicorns—lest you one day find yourself a pile of dusty bones.

A version of this post originally appeared on Brad’s blog.